In an era when software can be mirrored endlessly and delivered in seconds, a forgotten magnetic tape has delivered a sharper reminder: computing history still depends on chance, and on the people who know how to rescue fragile media before it disappears. The University of Utah has recovered and brought back to life the contents of a 1973 nine-track magnetic tape that, according to multiple reports and the preservation community tracking the find, contains what is believed to be the only complete known copy of UNIX Version 4 (Fourth Edition)—a pivotal release in the lineage that would go on to influence generations of Unix systems and, much later, GNU/Linux.

The significance is not just archival. UNIX v4 occupies a special place in the timeline because it is widely described as the first Unix edition where the kernel and core utilities were written in C, marking a turning point in how operating systems could be built and evolved. In 1973, that decision was far from obvious: squeezing every cycle out of assembly language was still standard practice, and rewriting foundational system code in a higher-level language could look like needless risk. With hindsight, it became part of the recipe that helped Unix spread and endure.

A storage-room find with unusually high stakes

The story begins in the most unglamorous way possible: a routine cleanup. In the University of Utah’s School of Computing, a Disco-era spool of tape turned up in storage—an artifact that, at first glance, could have been filed under “interesting but obsolete.” Instead, it triggered the kind of reaction usually reserved for lost manuscripts: this tape might contain a full system dump of UNIX v4, an edition that, for years, had not been known to survive in complete form beyond documentation fragments and manuals.

That distinction—code vs. complete system—matters. Early Unix distributions were ecosystems: source code, binaries, build tools, scripts, and assumptions about the hardware and boot environment all fit together in ways that don’t translate cleanly to modern machines. Recovering a complete dump is less like finding a single file and more like rediscovering a whole living specimen.

How to read a 50-year-old tape in 2025

Recovering data from a half-century-old tape is not “plug it in and copy the files.” Even finding a functioning nine-track tape drive can be difficult; keeping it calibrated enough to read aging media reliably is harder still. The recovery succeeded thanks to a technique that looks more like digital forensics than retrocomputing nostalgia.

According to the accounts published after the restoration, the archivist Al Kossow—a well-known figure in preservation circles—captured the tape’s raw analog read signal and digitized it using a multi-channel high-speed analog-to-digital converter, dumping the capture into roughly 100 GB of RAM for analysis. From there, the data could be reconstructed using specialized decoding software rather than relying on the tape hardware to deliver perfect digital output.

The key tool in that workflow is readtape, a program by Len Shustek designed specifically for situations where conventional tape-reading methods fail. Instead of treating the tape drive as a clean digital source, readtape works from digitized waveforms to recover bits and rebuild the original data stream—exactly the kind of approach needed when media has aged and error modes become unpredictable.

The moment everyone wanted: “It boots”

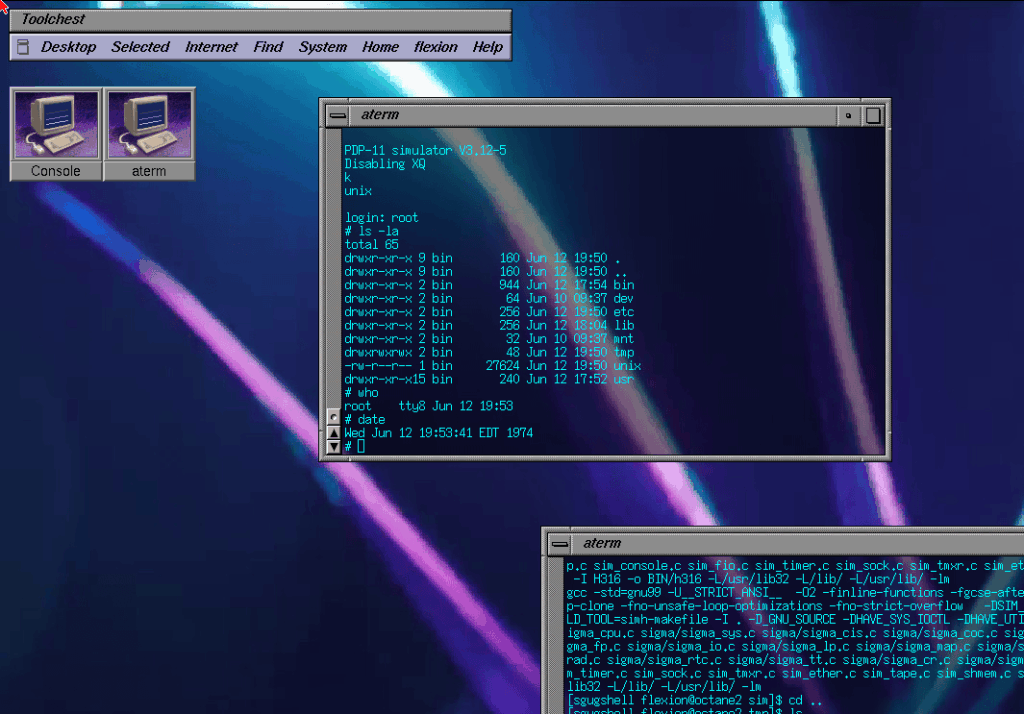

The most celebrated detail is not merely that the tape’s contents were extracted, but that the system is operational. In the preservation world, there is a difference between a pile of files and a coherent artifact. Here, the recovered UNIX v4 has been brought up in a workable environment—typically via PDP-11 emulation using tools such as SimH, as described in reporting around the recovery. That provides a direct window into the behaviors, assumptions, and practical realities of Unix in 1973, not just its documentation.

The TUHS (The Unix Heritage Society) mailing list—one of the central hubs for Unix history and restoration work—tracked the discovery, debated file timestamps and edition markers, and shared updates as extraction and boot testing progressed. Those threads underline something the headlines often miss: these recoveries are as much about patient verification and scholarship as they are about reading a tape.

Why UNIX v4 still matters: the C transition as a strategic move

Unix began at Bell Labs, and early versions leaned heavily on assembly language. By the time of the Fourth Edition, large portions of the system were being rewritten in early C. It’s common to compress the story into a simple slogan—“C made Unix portable”—but the reality is more nuanced. UNIX v4 still carried hardware-era constraints, yet the C shift established a durable pattern: operating systems could be expressed in a language that was both close enough to the machine for systems work and high-level enough to be maintained, evolved, and eventually moved across platforms more feasibly than pure assembly would allow.

For modern engineers, that moment is less a museum curiosity and more a reminder that software architecture decisions can outlive the hardware they were made for. The C transition helped create a codebase that could be studied, adapted, and reimagined—one reason Unix ideas seeped into universities, research labs, and later commercial systems across decades.

Digital preservation’s uncomfortable truth: history can hinge on luck

The recovery also highlights an unsettling reality: for a long time, what is now described as the only complete known copy of a milestone Unix release appears to have been sitting in storage, vulnerable to a move, a purge, or simple decay. Without communities like TUHS, preservation infrastructure like Bitsavers’ orbit of projects, and specialists capable of handling legacy media at the waveform level, foundational software history becomes a patchwork.

And yet, this story ends on a rare upbeat note: the tape was readable, the data was recovered, and the software can run again—turning what could have been a footnote into a living reference point for the origins of modern operating systems.

FAQ

What exactly is UNIX v4, and why is it historically important?

UNIX v4 (Fourth Edition Research Unix, 1973) is widely cited as a major milestone because it introduced a broader rewrite of the kernel and core utilities in early C, helping shape the evolution of Unix design and implementation.

Why do reports call this the “only complete known copy”?

Because, until this tape surfaced, the commonly held view in the Unix history community was that a complete, runnable UNIX v4 system dump had not survived—beyond partial artifacts like manuals and fragments. The tape’s restoration changes that “as far as is currently known.”

How can a 1973 magnetic tape be recovered if old tape drives are unreliable?

By digitizing the analog readout signal and reconstructing the data in software—an approach used here with a high-speed ADC workflow and Len Shustek’s readtape tooling, which is designed for degraded or hard-to-read tapes.

What does running UNIX v4 today enable for researchers and sysadmins?

It allows direct study of the system as it actually behaved—filesystem layout, utilities, kernel expectations, build practices, and design choices—providing a clearer picture of how early Unix thinking became the foundation for later Unix variants and Unix-like systems.

Sources (URLs)

- Tom’s Hardware — “Unix v4 recovered from randomly found tape at University of Utah…”

- At the U (University of Utah) — “Precious Computer Age relic turns up in U storage room”

- TUHS (The Unix Heritage Society) — mailing list thread and updates

- GitHub (Len Shustek) — readtape repository

- Gunkies (Computer History Wiki) — UNIX Fourth Edition entry

- Wikipedia — “Unix” and “History of Unix”

- Diomidis Spinellis — initial analysis of the recovered tape

Translation to spanish from Administración de sistemas.