Databases rarely become “the bottleneck” with a clean warning. It usually starts with a small latency drift. Then CPU spikes appear during peak hours. Lock contention grows. Connection pools begin to saturate. And eventually, the only thing the business hears is: “the site feels slow.”

For system administrators, this isn’t an academic discussion. The real questions are operational: which scaling technique to apply, in what order, with what failure modes, and how to run it safely without turning every change into an outage risk.

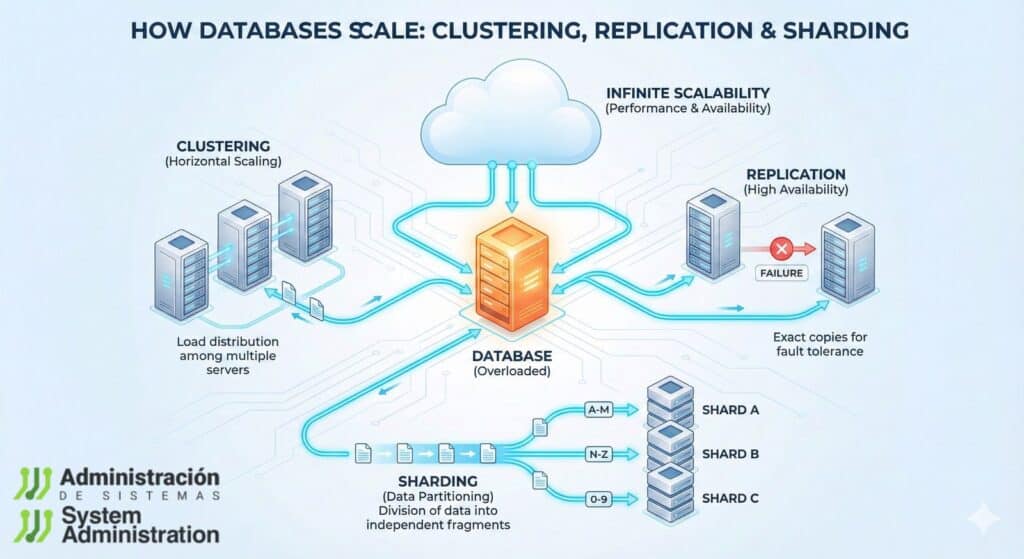

Three terms show up in almost every modern database architecture conversation: clustering, replication, and sharding. They are not interchangeable. Each solves a different problem—and each introduces a different kind of complexity. This guide explains them from a production ops perspective: availability, consistency, latency, backups, disaster recovery, observability, and change management.

Before You “Scale”: The Uncomfortable Checks That Save Months of Pain

A large share of “scalability problems” can be fixed without adding nodes. A sysadmin’s first job is to measure and rule out the basics:

- Is the limit CPU, RAM, storage I/O, or lock contention?

If storage latency is high, adding replicas might help reads, but it won’t fix write pressure. - Are queries and indexes sane?

A single missing index on a large table can crush even the best architecture. - Is the connection pool properly tuned?

Many outages are “too many connections” problems disguised as database performance. - Is analytics/reporting isolated from OLTP traffic?

Heavy reports running against production is a classic self-inflicted bottleneck. - Do you understand the workload shape?

Read-heavy scaling looks different from write-heavy scaling, and transactional writes are different from event ingestion.

Once these are under control and the system still hits limits, you enter the world of clustering/replication/sharding.

Replication: The First Step (and the Most Common)

Replication is usually the first real evolution of a production database: a primary node handles writes, while one or more replicas stay in sync and serve reads or secondary workloads (reporting, backups, batch jobs, staging refreshes).

What replication solves well

- Read scaling: offload

SELECTtraffic to replicas - Redundancy: a live copy exists, potentially reducing recovery risk

- Isolation: reporting/ETL can be moved away from the primary

What breaks if you don’t design for it

- Replication lag (async): replicas can serve stale data

- Inconsistent reads: if the app doesn’t know when it must read from primary

- Messy failover: promoting a replica is more than a command—it impacts routing, credentials, jobs, and data validation

Synchronous vs asynchronous replication: the trade-off that defines your system

- Synchronous: stronger consistency; higher latency; can impact availability if a replica blocks commits

- Asynchronous: better performance; introduces lag and non-zero RPO during sudden primary failure

A very common pattern is async replicas for read scaling plus a clear policy for “read-your-writes” flows that must hit the primary.

Ops tips for sysadmins

- Decide what traffic goes to replicas (safe reads only, not critical read-after-write flows)

- Monitor lag, replication thread state, and replication errors (engine-specific metrics apply)

- Maintain and test a failover runbook (including rollback procedures)

- Run failover drills regularly—what you don’t test will fail on the worst day

Clustering: Real High Availability, Real Operational Costs

Clustering is chosen when the main goal is minimizing downtime with automated continuity. If the primary node fails, service should continue with minimal disruption.

Common clustering models

- Active-passive: one node serves; one or more stand by

- Active-active: multiple nodes serve concurrently; requires coordination of writes and conflict control

- Shared-nothing: nodes have independent compute/storage; reduces shared dependencies but increases design requirements

The classic trap: “We have a cluster” ≠ “We have HA”

High availability is not your diagram. HA is:

- failure detection,

- leader election and promotion,

- client rerouting (VIP/DNS/proxy),

- defined consistency behavior during partitions,

- and post-failover validation.

If failover takes 5–10 minutes and requires manual steps, it may still be acceptable—but it is not the HA most teams imagine.

What a sysadmin should demand from an HA setup

- Quorum and fencing to prevent split-brain

- Explicit consistency model and behavior under network partitions (CAP trade-offs don’t disappear)

- Defined maintenance paths: rolling changes, upgrades, certificate rotation, controlled restarts

- Observability: node health, commit latency, queue depth, election stability

Sharding: True Horizontal Scale (and Application-Level Complexity)

Sharding splits a large dataset into smaller parts—shards—where each shard holds only a portion of the data. Unlike replication, sharding can scale writes as well as reads by distributing load across multiple primaries.

Sharding typically becomes necessary when:

- the dataset size or write volume is too large for a single primary,

- even after serious query/index optimization and strong hardware,

- and replication is no longer enough because the write bottleneck remains.

The critical piece: choosing the shard key

A poor shard key creates:

- hot shards (one shard overloaded while others idle),

- constant cross-shard queries,

- painful re-sharding projects.

Common distribution approaches:

- Range-based: intuitive, but can hotspot on “newest” ranges (time-based data)

- Hash-based: more even distribution, but harder range queries and some aggregations

- Directory-based: flexible routing via a lookup table, but adds a dependency that must be highly available

What changes operationally (this is where reality hits)

- Backups become multi-shard coordinated processes

- Global reporting usually requires separate pipelines (ETL/OLAP) or federation layers

- Schema changes become distributed operations

- Incident response becomes shard-aware (partial degradation must be handled cleanly)

Sharding is not just infrastructure. It’s a contract with the application.

Which One Should You Use? A Practical Ops-First Decision Rule

- If downtime is the pain → clustering / HA first

- If reads are the pain (SELECT/reporting) → replication first

- If writes or dataset size are the pain → sharding (and accept redesign)

And in mature systems, these are commonly combined:

- sharding to split datasets,

- replication inside each shard for read scaling,

- HA mechanisms per shard for continuity.

Consistency, Transactions, and Production “Surprises”

In distributed setups, consistency is no longer implicit. A sysadmin should force the conversation:

- Is stale read tolerance acceptable?

If async replication exists, define where it is safe. - Do you have cross-shard transactions?

If yes, you need patterns like sagas, queues, and compensating actions. Global ACID is not free. - What happens under network partitions?

Will you prioritize availability or consistency? The answer must be explicit.

Backups and Recovery: Where “Nice Architectures” Often Fail

Replication is not a backup. Replication can replicate:

- accidental deletes,

- logical corruption,

- destructive schema changes.

Practical best practices:

- Full + incremental backups (engine-appropriate methods)

- Consistent snapshots (coordinate with the database engine)

- Regular restore tests in an isolated environment

- Clear, measurable RPO/RTO, not just statements in a doc

With sharding, restores are more complex: you must rebuild a consistent state across shards.

Observability: The Minimum Monitoring You Need in Distributed Databases

More nodes means more failure points. A distributed database without observability is guaranteed long incidents.

Baseline monitoring typically includes:

- query and commit latency (p95/p99)

- CPU/memory/storage I/O and disk latency

- lock waits, deadlocks, long-running queries

- active connections and pool pressure

- replication lag and replication thread status

- quorum/election health and split-brain indicators

- WAL/binlog/redo size and retention behavior

- per-table/partition/shard growth

Alerts should be predictive, not cosmetic: “disk at 85% with fast growth” is more valuable than “CPU high for 2 minutes.”

Runbooks: The Real Difference Between “Designed” and “Operable”

In production, the winning architecture is often the one you can operate at 03:00 with no improvisation.

Runbooks should cover:

- planned vs unplanned failover

- replica promotion and integrity validation

- safe reintegration of the old primary (avoid “zombie primary” disasters)

- credential/certificate rotation without downtime

- backwards-compatible schema changes

- maintenance tasks (reindex, vacuum, compaction) without collapsing performance

- traffic surge handling (rate limiting, graceful degradation, queues)

Conclusion

Clustering, replication, and sharding are practical responses to inevitable limits of a single database server. Replication is typically the first step: it improves read scaling and adds redundancy. Clustering focuses on continuity and failover, demanding quorum and anti-split-brain discipline. Sharding enables massive horizontal growth, but it requires application-aware routing and distributed operations.

For sysadmins, the winning strategy is pragmatic: measure first, keep it as simple as possible, scale in stages, and document/verify procedures. In production, stability comes from operability—not from diagrams.

FAQs

1) In a growing system, should replication or clustering come first?

Most environments start with replication, because it’s usually easier and quickly improves read performance and redundancy. Clustering becomes essential when downtime constraints tighten and failover must be automated.

2) How do you prevent split-brain in high availability setups?

By using quorum-based leader election, fencing, and strict rules that ensure only one node can act as primary at a time. Split-brain prevention is mandatory, not optional.

3) What’s the earliest warning sign that async replication is becoming risky?

A sustained, increasing replication lag, especially when paired with I/O saturation or replication thread backlogs. If lag grows and doesn’t recover, your failover RPO may exceed what the business can tolerate.

4) When does sharding become unavoidable?

When write throughput or dataset size exceeds what a single primary can handle—despite strong hardware and solid optimization—and replication can’t relieve the main bottleneck because the bottleneck is writes and state.