For years, platforms like Heroku, Vercel, or Railway have sold a compelling idea: push your code, set a few environment variables, and deploy—no servers to babysit, no networking headaches, no Kubernetes learning curve. The catch is that convenience often comes with two downsides: costs that rise as you scale, and vendor dependence on a provider that can change prices, limits, and rules at any time.

That’s where dFlow comes in. It’s an open-source project that positions itself as an alternative to Railway/Vercel/Heroku—with one crucial difference: it’s designed to run on your infrastructure (or on whatever cloud provider you choose).

What dFlow is—and what it’s trying to fix

dFlow presents itself as a self-hosted deployment and infrastructure platform aimed at teams that want to keep control of their servers without taking on the full complexity of traditional DevOps. In its own materials, the message is straightforward: an open-source alternative you can host yourself and use in real production setups.

The scope goes beyond “just deploy”:

- A dashboard to manage projects, domains, and environments

- Automated workflows: deployments, scheduled tasks (cron), logs, and basic observability

- Support for common databases and related services

- Multi-server management, focused on reducing day-to-day operational friction

A notable angle: multi-server orchestration “without Kubernetes”

One of dFlow’s most distinctive positioning points is technical: it highlights multi-server orchestration over SSH and the idea of scaling “without containers or Kubernetes” in the classic orchestration sense.

That doesn’t mean “no Docker.” In fact, for self-hosting dFlow itself, the recommended approach uses Docker Compose. The emphasis is that you shouldn’t need to assemble a complex stack of tools and YAML files just to handle the basics of deployment and operations.

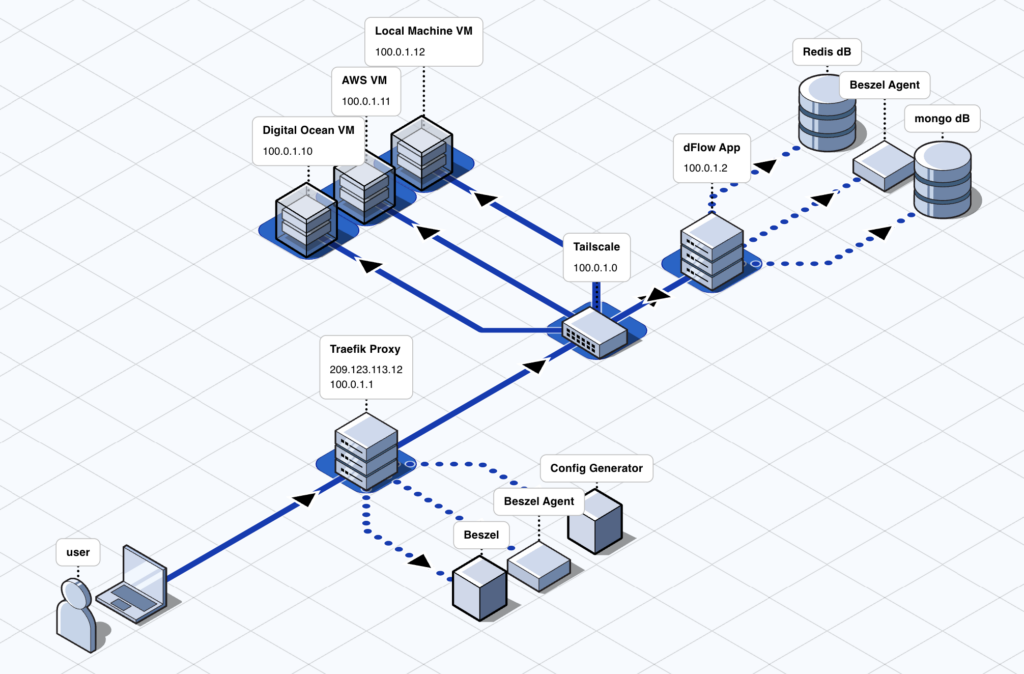

Private networking: “Zero Trust” with Tailscale

Another recurring theme in dFlow’s messaging is private networking. The project points to Zero Trust support via Tailscale (end-to-end encryption) and claims you can operate without relying on SSH keys.

For teams running internal services or customer apps in their own infrastructure, this can be a big deal: less exposure to the public internet and a workflow aligned with modern self-hosting—operate inside a private mesh whenever possible.

What you can deploy: repos, images, and databases

dFlow promotes “deploy anything”: it can deploy public or private Git repositories, Docker images, and common databases such as Postgres, MongoDB, MySQL/MariaDB, and Redis.

It also includes:

- RBAC (role-based access control) to separate admins and end users

- Templates to kick-start deployments with popular open-source stacks

- White labeling so agencies can adapt branding and domains for client-facing use

What’s under the hood when you self-host it

If you self-host, the documentation describes a Docker Compose setup with several components: Traefik as the reverse proxy (with automatic SSL via Let’s Encrypt), MongoDB for persistence, Redis for cache and background jobs, Beszel for monitoring, a config generator for dynamic routing, and Payload CMS as a core part of the platform.

This matters for two reasons:

- It gives you a clear view of the “control plane” you’re deploying (it’s not a single binary).

- It explains why dFlow may need meaningful resources if you want a production-grade environment.

Requirements: the fine print is worth reading

In the GitHub README, dFlow lists fairly modest minimums (Ubuntu 22.04/24.04; from 1 vCPU/2 GB RAM, with 2 vCPU/8 GB recommended). But the official installation docs include a more demanding recommendation for the server (minimum 6 vCPU and 12 GB RAM, SSD/NVMe storage), along with ports 80/443, Docker 20.10+, and Docker Compose 2+.

A practical interpretation: the README minimums are likely fine to test and explore, while the official guide aims at a more robust setup—especially if you’ll manage multiple apps and users.

Project status: fast iteration and a clear focus on migrations

dFlow is clearly evolving. Its GitHub releases show ongoing iteration, which typically signals a project moving quickly.

Its public roadmap also highlights a priority that makes sense for its target audience: making it easier to move from Railway, including automation for migrating configurations and services, plus features like database migrations between servers and backup options for external databases.

Who it’s best for

dFlow appears to fit three profiles particularly well:

- Indie developers who want to run apps on 1–3 servers without becoming a full-time SRE

- Startups that need automated deployments but don’t want the cost curve of hosted PaaS as they scale

- Agencies managing multiple client projects who benefit from RBAC and white labeling

In every case, the underlying pitch is the same: keep control (often reducing cost) without giving up the “push-to-deploy” experience.

How to try it without overthinking

If you want to get a feel for dFlow, there are two common paths:

- Try a demo/hosted instance to see the UI and deployment flow before touching servers

- Self-host it: the project offers an installer that’s convenient for quick setup, while the docs position Docker Compose as the stable route. As with any “curl | bash” install, it’s smart to understand what it’s doing before using it for production.

FAQ

Does dFlow replace Kubernetes?

Not exactly. dFlow aims to avoid the complexity of traditional orchestration for common deployment and operations workflows, and it emphasizes multi-server orchestration over SSH.

Can I deploy databases as well as applications?

Yes. The project mentions support for databases like Postgres, MongoDB, MySQL/MariaDB, and Redis, alongside Git repos and Docker images.

Is it production-ready or still early?

It provides a “production-grade” Docker Compose setup (Traefik, Redis, MongoDB, monitoring), but it’s also evolving quickly and its roadmap shows features still in progress.

What’s the role of Tailscale here?

It underpins dFlow’s Zero Trust/private networking story: end-to-end encrypted connectivity and an operating model that reduces reliance on classic SSH key workflows.