Microsoft’s announcement about the definitive retirement of Windows Internet Name Service (WINS) marks the end of a historic component in Windows networks. For many administrators, it was already a “useful fossil”, but now it has a clear expiration date: Windows Server 2025 will be the last version to include WINS, and the feature will only remain under standard support until November 2034.

Behind this move lies a story that begins in the 1990s, when the Internet was just starting to take off and companies were struggling to control a swarm of NetBIOS names in their local networks. Understanding WINS’ origins helps explain why Microsoft is now pushing so hard towards a world where DNS is the only reasonable alternative.

The 90s: when NetBIOS was everything

In the first large corporate networks based on Windows, most traffic revolved around NetBIOS, a simple, flat naming system designed for local networks. Machines were identified by short names like SERVER1 or ACCOUNTING, and they discovered resources via broadcast messages.

This worked fine while networks were small. But as they grew, problems appeared:

- More machines meant more broadcasts and more congestion.

- Duplicate names or conflicts became harder to troubleshoot.

- Linking remote sites over WAN connections made broadcast-based discovery impractical and inefficient.

In that context, Microsoft introduced WINS, a centralized name resolution service capable of mapping NetBIOS names to IP addresses dynamically. Windows clients registered their name with one or more WINS servers, and from that moment on they no longer depended solely on broadcasts to find each other.

For many companies at the time, WINS was the piece that allowed them to move from a small office network to corporate infrastructures with hundreds or thousands of devices without collapsing the network.

How WINS worked and why it was so useful

In practice, WINS behaved like a NetBIOS name database:

- Each machine registered its name and IP address at startup.

- WINS servers kept that information updated, with expiration times and periodic renewals.

- It was possible to configure primary and secondary WINS servers, as well as replication between them for high availability.

In an era when many file servers, printers and line-of-business applications only understood NetBIOS names, WINS provided:

- Less broadcast traffic on the local network.

- Name resolution across subnets and remote sites, something very complicated to achieve with pure NetBIOS.

- A central point where administrators could see what names existed, which IP they mapped to, and when they had been registered.

For all these reasons, WINS became a standard component in Windows NT deployments and later in Windows 2000 and 2003. Almost every corporate network diagram included, somewhere, one or several WINS servers.

The arrival of DNS and the turn towards the Internet

While WINS was solving internal network problems, the outside world started speaking another language: DNS (Domain Name System).

DNS was not designed with NetBIOS in mind, but with the Internet:

- It uses hierarchical domain names such as

company.comorsales.company.local. - It is distributed and scalable, built to grow without relying on a single central server.

- It allows internal and external services to be integrated under a single naming logic.

In the late 90s and early 2000s, Microsoft chose to align its strategy with that standard. The decisive step came with Windows 2000 and Active Directory, where:

- The directory and many Windows services began to depend on DNS to function properly.

- Service records (

SRV) and dynamic updates made it possible to locate domain controllers and other key resources without resorting to NetBIOS.

From then on, WINS was pushed into two main roles:

- Acting as a crutch for legacy applications still using NetBIOS names.

- Covering some transition scenarios, especially in mixed networks where modern clients coexisted with old systems.

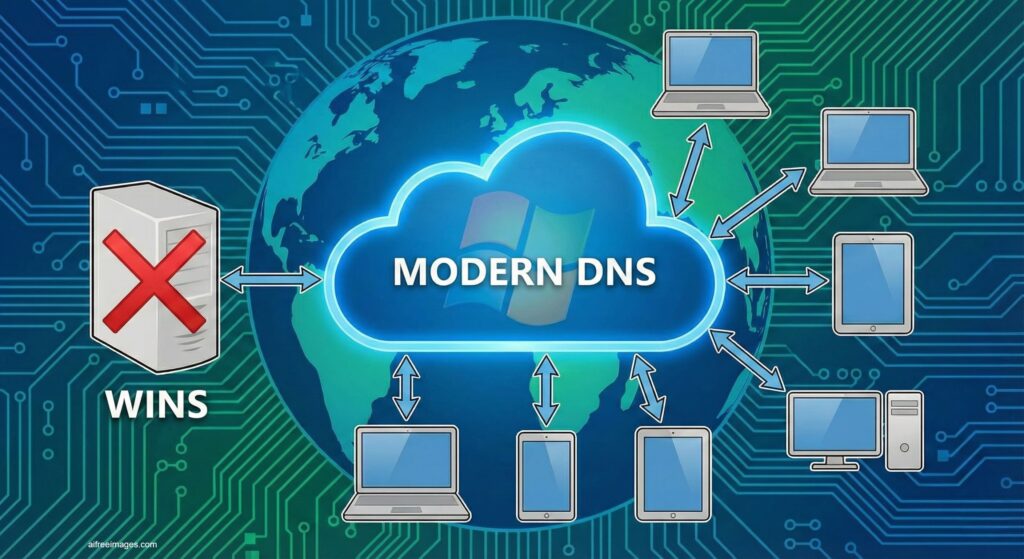

WINS vs. DNS: why one is leaving and the other stays

Microsoft’s decision to finally “pull the plug” on WINS is not just historical, but deeply technical. Compared to DNS, the old technology clearly falls behind.

Scalability and structure

- WINS uses a flat name space, with no hierarchy. As the network grows, the database gets more complex and name management becomes fragile.

- DNS organizes names in a hierarchical structure, with delegated zones and subdomains. This makes it easier to distribute load, delegate responsibilities and grow in an orderly way.

Standard and compatibility

- WINS is essentially a proprietary Microsoft solution, tightly bound to NetBIOS and classic Windows networks.

- DNS is defined by open standards (RFC 1034 and 1035) and is the common language of the entire Internet, which ensures interoperability with operating systems, network devices and services from virtually any vendor.

Security

- WINS lacks modern mechanisms to protect itself against attacks such as spoofing or response tampering.

- DNS can be strengthened with DNSSEC, which adds cryptographic signatures to responses to prevent cache poisoning and ensure data integrity.

Future of applications

- Modern applications, cloud services and key platforms such as Active Directory already depend on DNS. WINS barely appears in current documentation, beyond legacy compatibility notes.

- Many software vendors no longer test their products in environments that depend on WINS, which increases the risk of bugs in older setups.

In this landscape, WINS has become more of a drag than a help. Keeping it alive means dragging complexity and security risks that no longer make sense in modern networks.

The long goodbye: from deprecated feature to full retirement

Microsoft has chosen a strategy of slow but clear transition.

- Deprecation announcement

- WINS was officially marked as deprecated in Windows Server 2022.

- The feature remained available and supported, but with no new capabilities or future evolution.

- Last stop: Windows Server 2025

- Windows Server 2025 will be the last LTSC release to include WINS.

- The role will still be installable and under standard support throughout that product’s lifecycle.

- End of standard support

- Windows Server 2025’s lifecycle extends to November 2034. That is the maximum horizon Microsoft offers to those who still depend on WINS.

- Future versions without WINS

- From then on, future Windows Server versions will no longer include the role, the MMC snap-in, or related APIs.

The message for organizations is unambiguous: do not design any new architecture that depends on WINS, and existing deployments should already have an exit plan.

What organizations still using WINS should do now

Even though the support window looks long, core network migrations are rarely trivial. Microsoft recommends several steps for companies still relying on WINS:

- Inventory NetBIOS and WINS usage

- Locate servers that have the WINS role installed.

- Review applications, scripts and systems that still use NetBIOS names instead of DNS names.

- Design a robust DNS strategy

- Consolidate internal DNS servers with high availability.

- Use conditional forwarders, split-brain DNS and search suffix lists to cover scenarios previously solved by WINS.

- Modernize legacy applications

- Wherever possible, upgrade or replace products that depend exclusively on NetBIOS.

- For critical systems that cannot be touched in the short term, isolate them in well-controlled network segments with clear retirement plans.

- Avoid dangerous shortcuts

- Do not rely on static

hostsfiles as a permanent solution: they do not scale, are hard to maintain and can cause inconsistent behavior.

- Do not rely on static

A change of era for Windows networks

The retirement of WINS is not just a technical detail, but a symbol of how networks have changed over the past decades. Companies have moved from closed local networks to hybrid, multicloud and global environments, where the boundaries between internal and external networks are increasingly blurred.

In that scenario, a flat, NetBIOS-based naming system no longer fits. DNS, with its ability to span from on-premises servers to cloud services, becomes the logical backbone on which to build the next generation of infrastructures.

For administrators who have spent years dealing with WINS servers, replication settings and stale records, the announcement carries a dose of nostalgia. But it’s also an opportunity: to use the Windows Server 2025 lifecycle to close the NetBIOS and WINS chapter for good, and commit to a naming architecture aligned with the present and future of networking.

Frequently asked questions about WINS, its retirement and the migration to DNS

Is it still safe to use WINS while it’s under standard support?

As long as WINS is part of Windows Server 2025 and within its standard support lifecycle, it will continue to receive maintenance under the product’s general policy. However, it is an old technology without advanced protection mechanisms, so it is not advisable to keep it any longer than strictly necessary if you want a security posture aligned with current best practices.

What problems can appear if a company delays migrating from WINS to DNS?

The longer you postpone migration, the more likely hidden dependencies will accumulate: internal apps, scripts, printers or old servers nobody remembers that still use NetBIOS. This can cause unexpected outages when you upgrade infrastructure, change operating systems or integrate cloud services. In addition, future support for many third-party products may stop considering WINS-based setups at all.

Is it possible to replace WINS with DNS only, without touching applications?

In many cases, yes. By properly tuning DNS search suffixes, setting up internal zones and conditional forwarders, clients can resolve names that previously depended on WINS. However, if an application uses NetBIOS calls directly or assumes WINS is present, you may need to update or replace it to guarantee full functionality in a DNS-only environment.

What practical advantages does DNS offer over WINS in a modern network?

DNS allows you to manage host and service names in a hierarchical, distributed and standardized way, integrating local machines, cloud apps and public services in a single naming scheme. It makes high availability easier, supports load balancing, integrates with Active Directory, and enables security features like DNSSEC. In short, it reduces operational complexity, improves scalability and aligns with how the Internet and most current applications actually work.

source: support.microsoft