Most new Linux distributions follow a predictable recipe: pick a popular base, add a desktop, throw in some theming, and ship. Sometimes it works; often the distro quietly vanishes in a year.

ObsidianOS is different. It’s not trying to be “Arch with KDE but prettier”, it’s trying to rethink how updates, rollbacks and system integrity work on a desktop system — borrowing ideas from ChromeOS and Android and adapting them to a traditional Linux environment.

Yes, it’s Arch-based. But the real story is an A/B partition layout on plain ext4, plus a set of Rust-powered tools that treat your system more like something you can safely “version” and roll back, instead of something you’re scared to update at 2 a.m.

A/B partitions on the desktop: two roots, one lifeline

The core of ObsidianOS is its A/B partition scheme. Instead of a single root filesystem, you get two root partitions: slot A and slot B. You boot from one, while the other sits idle.

When a system update arrives, the inactive slot is the one that gets written to. If the update goes well, the next reboot switches to that freshly updated slot. If something breaks — kernel issues, a bad package, a misconfigured system — you simply boot back into the previous, known-good slot.

No btrfs snapshots, no complicated rollback tooling, no grub-repair marathons. Just “go back to the other system”. It’s the same principle that keeps ChromeOS and many Android devices resilient, brought to a general-purpose Linux desktop.

What makes this unusual is that ObsidianOS does it all on ext4, not on copy-on-write filesystems or fancy snapshot layers. It leans on a very familiar stack and focuses the magic in the update and boot logic instead.

Four editions and a homegrown installer

Despite being a relatively young project, ObsidianOS already comes in several flavours:

- Base Edition – minimal, with a TUI installer aimed at power users.

- KDE Edition – the recommended one, with a clean Plasma desktop.

- COSMIC Edition – based on System76’s COSMIC desktop, currently in beta.

- Void Edition – for those who want Void Linux as the base with Obsidian’s tooling on top.

The KDE and COSMIC images ship a custom installer built with Qt 6 and Python, rather than relying on Calamares. The wizard walks you through:

- Picking the target disk.

- Automatically setting up the A/B partition layout.

- Choosing a system image.

- Timezone and keyboard.

- Bootloader configuration.

The interface still feels young in places — some dialogs could be clearer — but it handles the A/B scheme behind the scenes without drowning the user in jargon.

Hardware requirements are modest on paper (2 GB RAM, 64-bit CPU, ~20 GB storage), though in practice you’ll want more memory for a comfortable KDE experience. One important detail: ObsidianOS is UEFI-only and systemd-based, so it’s not targeted at very old hardware.

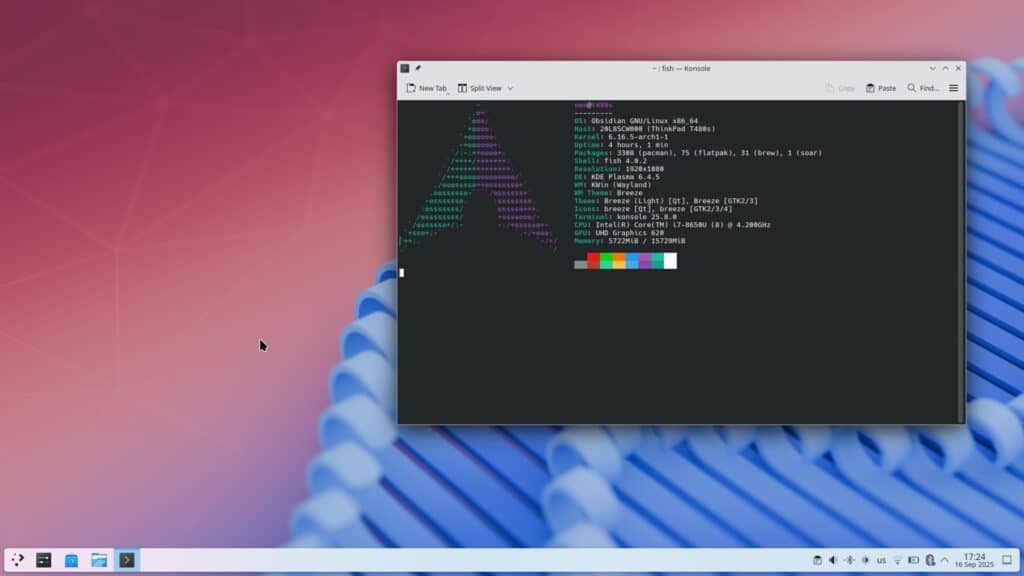

First boot: a clean Arch environment… with a twist

The first boot into ObsidianOS KDE looks and feels like a well-tuned Arch desktop. Plasma is close to vanilla, with no heavy theming or aggressive UI overhauls. The application launcher, system settings and default tools are what you’d expect if you’d set up Arch with KDE yourself.

The distinctiveness appears when you open the ObsidianOS Control Center, a Qt GUI front-end for the obsidianctl command-line tool. That’s where the A/B world becomes visible:

- It shows which slot (A or B) you’re currently running.

- Lists available system updates.

- Offers rollback options to the other slot.

- Exposes logs and system information related to updates and system state.

This is where ObsidianOS starts to feel like its own thing rather than “Arch with an unusual disk layout”.

User-mode overlays: layering changes without touching the kernel

Beyond the A/B layout, the project introduces user-mode overlays, an experimental system written in Rust. In plain language, it intercepts libc calls to create a layered filesystem behaviour entirely in user space — no kernel modules, no special filesystem support.

Practically, this gives you:

- A “layer” on top of the root filesystem.

- The ability to apply and roll back changes cleanly.

- A kind of sandbox for certain operations, with the base system protected unless you explicitly commit changes.

This overlay mechanism also powers another core component: opm (Obsidian Package Manager), a Rust-based package tool that works alongside pacman.

When you install a package with opm:

- It pulls the package from the Arch repositories.

- It builds an overlay image from that package.

- It applies that overlay on top of the system.

Instead of sprinkling changes directly into the root, installs become layered operations. It’s a radically different approach from what you see in most distros, and hints at a future where package-related breakage is far easier to contain and reverse.

For Arch purists this might sound heretical; for tinkerers and power users, it’s very intriguing.

Plugins and events: reacting to your hardware and system state

ObsidianOS also ships a plugin system, again written in Rust, that lets scripts react to system events such as:

- Battery level changes.

- Device plug/unplug.

- Other hardware or system triggers.

Linux has long had ways to do this (with udev rules, ACPI hooks, systemd units and so on), but ObsidianOS tries to unify this into a single, cohesive framework. The goal is to make it easier to automate reactions without forcing users to dig through several separate subsystems.

Daily use and performance

Since it’s based on Arch, performance behaves as expected:

- Fast boot times.

- A responsive KDE desktop.

- Recent kernels and packages.

- Access to the huge Arch repository ecosystem.

The KDE edition stays relatively lean and avoids unnecessary preinstalled software. The COSMIC edition is still beta, so it’s more of a playground for now than a daily driver.

The experimental components — overlays, opm, plugins — generally work, but they’re clearly aimed at people comfortable checking logs and understanding what’s happening under the hood. That’s not a flaw; it’s just the current maturity level of the project.

Ambitious, experimental… and not for everyone (yet)

To keep things realistic, it’s worth stressing a few points:

- Small team, young project – longevity is always a question mark with smaller distros.

- Experimental building blocks – overlays, the custom package manager and plugin system are powerful but still evolving.

- A/B on the desktop is unusual – not bad, just unfamiliar. Some users will love it; others will prefer more conventional setups.

For absolute beginners who just want a stable Linux to get things done, this is probably not the best choice right now.

For people who install Arch manually for fun, enjoy NixOS or immutable systems like Fedora Silverblue and openSUSE MicroOS, and are curious about transactional-style updates without leaving the Arch universe, ObsidianOS hits a very interesting middle ground.

It’s one of the rare Arch-based distros that genuinely tries to solve a hard, old problem — safe updates and rollbacks — instead of simply remixing themes and desktops. If the team keeps pushing its A/B approach, user-mode overlays and opm forward, ObsidianOS could become one of the more innovative Linux projects to emerge from the Arch ecosystem in quite a while.

ObsidianOS – quick FAQ

How is ObsidianOS different from a typical Arch-based distro?

ObsidianOS is built around an A/B root partition layout and user-mode overlays, plus its own tools (obsidianctl, opm, plugin framework). The goal is to make updates, rollbacks and system state much safer and more predictable than in a traditional rolling-release install.

Is ObsidianOS suitable for Linux beginners?

Not really. While the graphical installer helps, many of its strengths require understanding concepts like slots, rollbacks, overlays and Arch’s packaging. It’s better suited to intermediate or advanced users.

What editions are available?

There’s a minimal Base Edition, a KDE Edition (the recommended one), a COSMIC Edition that’s still in beta, and a Void Edition for those who want a Void Linux base with Obsidian’s tooling on top.

Who should consider trying ObsidianOS today?

Tinkerers, Arch fans and power users who like the idea of transactional-like updates, safer rollbacks and Rust-powered tooling — all while staying close to the Arch ecosystem and using familiar filesystems like ext4.

Image source Reddit