In modern infrastructure, cache is one of those quiet components that decides everything: whether a site feels instant or sluggish, whether an API survives a traffic spike or collapses, and whether scaling means smart engineering or just buying more servers. That’s why any newcomer claiming “faster than Redis” instantly draws attention — and skepticism.

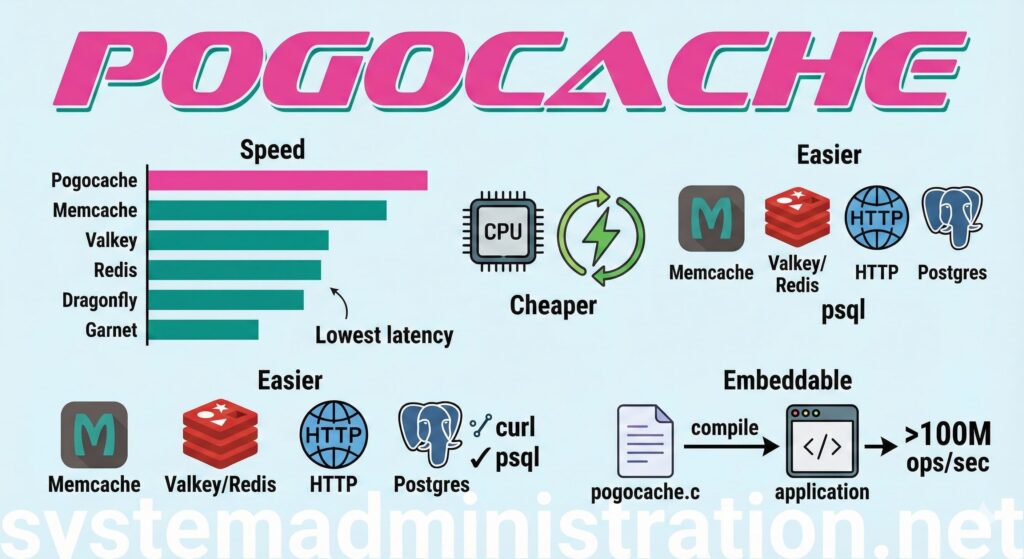

Pogocache is positioning itself as exactly that kind of challenger: a cache built from scratch with a single-minded focus on low latency and CPU efficiency. The project’s pitch is straightforward: fewer CPU cycles per request, better scaling across cores, and an easier path to adoption because it can speak multiple protocols out of the box.

A cache server that “speaks your tools,” not just your library

One of Pogocache’s most practical ideas isn’t just performance — it’s compatibility.

Instead of forcing teams into one client ecosystem, it supports multiple wire protocols:

- Memcache text protocol

- RESP (Valkey/Redis-style)

- HTTP (PUT/GET/DELETE)

- Postgres wire protocol (so you can even use tools like

psql)

This matters because it lowers the cost of evaluation. A team can test Pogocache with existing tooling — curl, redis-cli/valkey-cli, or psql — without a rewrite or a new SDK rollout. In real operations, that friction is often what kills “promising” infrastructure projects before they ever reach production.

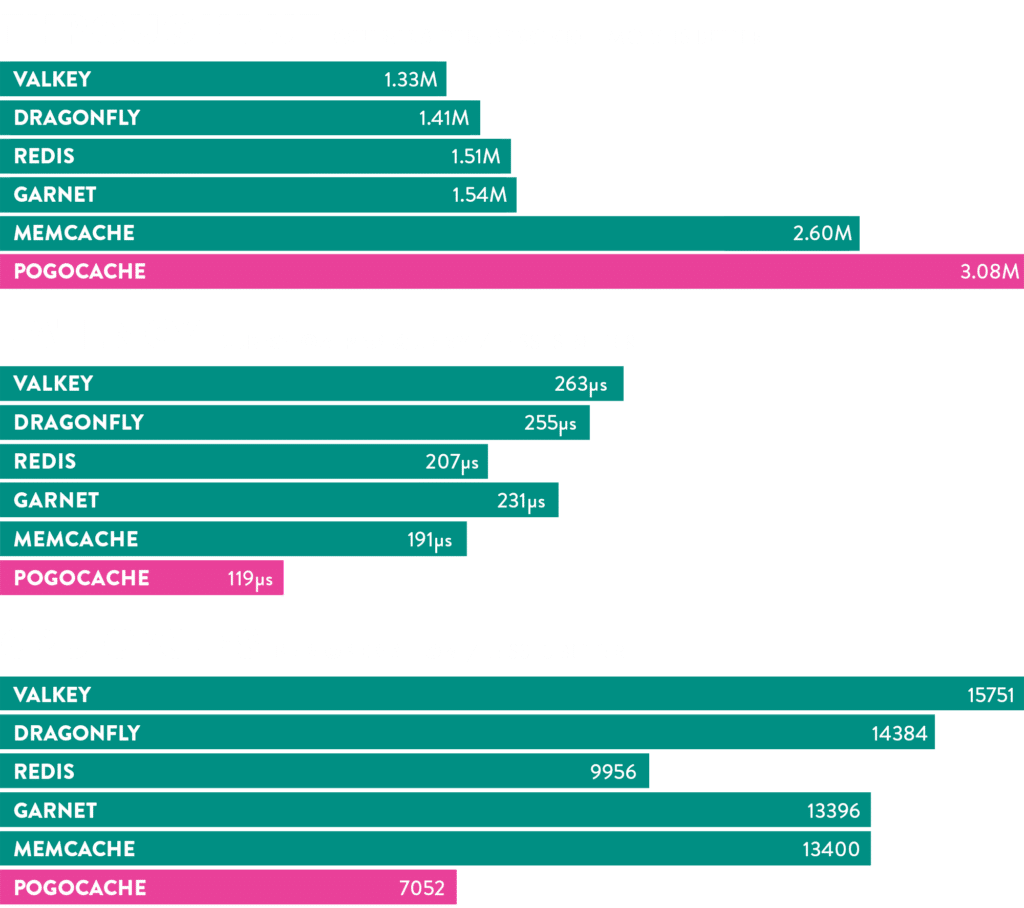

The headline claim: 3.08M QPS on an AWS Graviton instance

Pogocache leans heavily into benchmark comparisons. In its published numbers, it claims 3.08 million QPS in an 8-thread benchmark on an AWS c8g.8xlarge, outperforming Memcache, Redis, Valkey, Dragonfly, and Garnet in that specific chart.

Those figures come with important context, and the project’s benchmark companion repository is unusually transparent about methodology:

- Testing uses memtier_benchmark

- Persistence is off (no disk I/O)

- All connections are local (UNIX named pipes)

- The machine is a 32-core ARM64 instance

- Each benchmark runs 31 times, and the median is used

- Latency is tracked across percentiles up to 99.99th, plus MAX

- CPU cycles are measured via Linux perf

- Server and load generator are pinned to separate CPU ranges

That transparency doesn’t “prove” universal superiority, but it does make the results easier to interpret than the usual marketing benchmark slide. Still, any operator will recognize the gap between a clean lab test and messy production realities: different payload sizes, real networks, mixed workloads, eviction pressure, and long-tail latency under contention.

Under the hood: shards, Robin Hood hashing, and event-driven networking

Pogocache is written primarily in C and describes an architecture optimized for fast key-value operations:

- Data is stored in a sharded hashmap, often configured around 4,096 shards

- Each shard maintains its own hashmap using open addressing with Robin Hood hashing

- Shards are protected by a lightweight spinlock during operations

- Hashing uses a 64-bit function with a crypto-random seed generated at startup

- Keys can optionally use a bespoke “sixpack” compression (6 bits per byte) as a storage optimization

On the networking side, the system starts with a thread count based on CPU cores, then builds an event queue per thread (epoll on Linux, kqueue on macOS). Connections are distributed across queues round-robin, and the design can optionally use io_uring on Linux for batching reads/writes.

It’s a familiar philosophy in high-performance servers: keep hot paths small, keep memory structures tight, and avoid expensive coordination across threads whenever possible.

Expiration, eviction, and memory pressure handling

Pogocache supports TTL-based expiration, but the more operationally important piece is what happens under memory pressure:

- Expired keys become unavailable and are cleared through periodic sweeps

- When memory runs low, inserts may evict older entries using a 2-random strategy

- The design claims it tries to ensure evicted/expired entries do not accumulate beyond a portion of total cache memory

These details aren’t “flashy,” but they’re exactly where cache systems win or lose trust in production — especially when traffic patterns shift suddenly.

Two deployment styles: server mode or embedded mode

Pogocache also offers something unusual in this segment: an embeddable mode.

Alongside the server, the repository includes a self-contained C implementation (pogocache.c) that can be compiled directly into an application. The argument is simple: no network hop, no protocol parsing overhead — just direct function calls. The project claims extremely high ops/sec in embedded mode, framing it as “raw speed” compared with a traditional cache daemon.

In practice, embedded caches can be attractive for latency-sensitive systems, but they also shift complexity into the application lifecycle (versioning, memory boundaries, crash domains, observability). For most teams, server mode will remain the default, but having both options is a differentiator.

Security basics: TLS and authentication

Pogocache includes pragmatic security features that most operators will consider table stakes:

- TLS/HTTPS support via runtime flags

- Optional auth password/token that clients must provide

That doesn’t replace network segmentation or zero-trust design, but it does make it easier to deploy safely in environments where “a cache on an open port” is no longer acceptable.

Licensing: MIT, with a clear commercial support path

The project is released under the MIT license, which removes many adoption barriers for companies wary of restrictive licensing. It also clearly advertises commercial support options, which is often a signal that the maintainers are thinking beyond hobbyist use.

The real question: speed is easy to claim — durability is hard to prove

Pogocache is making all the right moves to get attention in 2026:

- Performance-first messaging

- Multi-protocol compatibility that reduces adoption friction

- Transparent benchmarking methodology

- A low-level design that sounds credible to system engineers

But cache software doesn’t earn its reputation on charts. It earns it through long-running deployments, failure scenarios, operational tooling, and how it behaves when everything goes wrong: bursts, partial outages, noisy neighbors, memory fragmentation, kernel quirks, and real traffic distributions.

If Pogocache can pair its performance claims with production-grade stability and a growing ecosystem, it could become a serious option — not necessarily as a universal Redis replacement, but as a specialized low-latency cache layer where CPU cycles and tail latency are the business.

For now, it’s one of the more interesting “built from scratch” cache projects to watch — especially because it’s not just trying to be fast, but trying to be easy to test with the tools teams already use.