Some technologies vanish quietly. Others refuse to die—because the real world keeps using them long after the consumer market has moved on. GPIB, short for General Purpose Interface Bus, is one of those stubborn survivors.

Originally introduced by Hewlett-Packard in 1972 (often referred to as HP-IB), GPIB became a fixture in laboratories and research environments well before anyone had heard of USB-C, Wi-Fi, or cloud dashboards. Now, in a twist that feels almost poetic for the open-source world, that decades-old connector is finally getting something it never properly had in Linux: stable, official driver support in the mainline kernel—not experimental, not “maybe,” but real, maintained integration.

What is GPIB, and why did it matter so much?

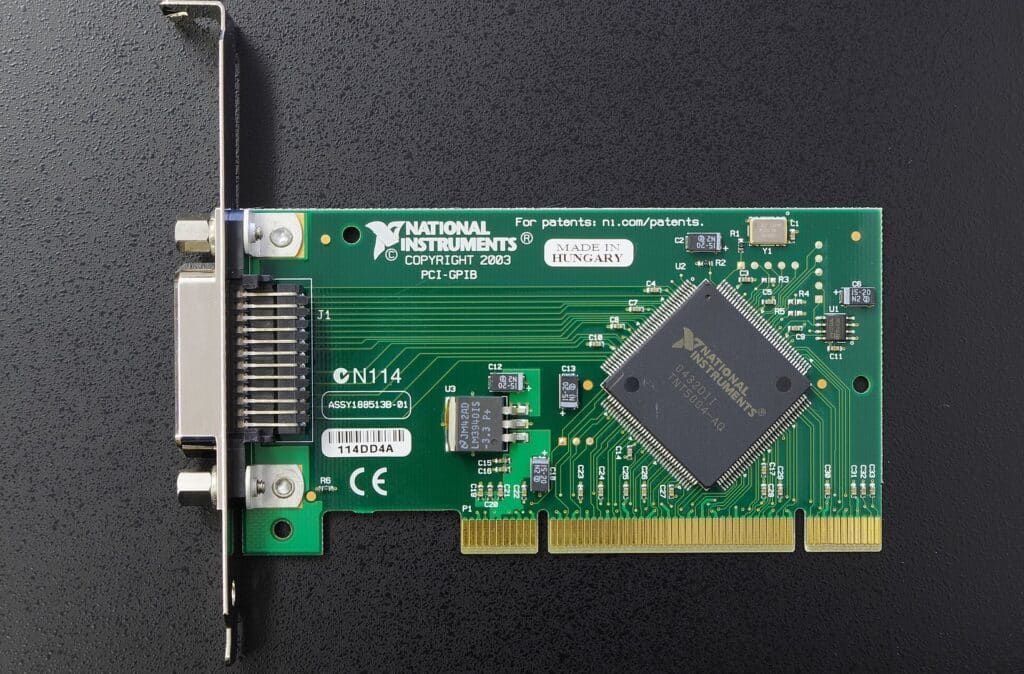

To the average user, GPIB looks like a chunky, old-school interface from another era. But in the 1970s and 1980s, it was close to royalty in technical environments. It was built to connect computers to test and measurement instruments—think oscilloscopes, multimeters, signal generators—so engineers could automate experiments, collect readings, and control equipment reliably. Over time, the technology was standardized as IEEE-488, which helped it spread far beyond HP’s own ecosystem.

GPIB wasn’t designed to be fashionable; it was designed to be dependable. It supported multiple devices on a shared bus and was meant for the kind of environments where “it just works” matters more than sleek design.

And, surprisingly, it didn’t stay confined to labs. Variants and implementations of IEEE-488 appeared in parts of the home computing world too—often mentioned alongside classic systems like the Commodore 64—which only adds to the sense that this was one of those foundational “glue” technologies that quietly connected generations of hardware.

The big news: Linux 6.19 makes GPIB “officially stable”

Linux has had all kinds of support for legacy hardware over the years, but GPIB has lived in a particular corner of the kernel: staging.

If you’re not familiar with kernel development, “staging” is basically Linux’s waiting room. Drivers can live there while they’re being cleaned up, reviewed, modernized, and brought up to the standards expected in the “real” kernel. That doesn’t necessarily mean they’re unusable—it means they’re not considered fully mature or fully integrated.

According to reports from kernel watchers and the Linux community, the GPIB driver has now been promoted out of staging and into the mainline kernel for Linux 6.19, after roughly a year of cleanup and improvements.

Kernel developer Greg Kroah-Hartman—who oversees staging—highlighted that this is one of the notable staging promotions for the 6.19 cycle, with gpib moving into the “real” portion of the kernel.

For anyone still using GPIB equipment today, the meaning is simple: less fragility across kernel upgrades, better long-term maintenance prospects, and fewer workarounds.

Why would anyone still use GPIB in 2025?

Because in science, engineering, and calibration work, hardware lifecycles don’t look like smartphones.

A lab instrument can remain useful for decades. Sometimes it’s because the device is expensive; sometimes because it’s deeply integrated into workflows; and often because it’s been calibrated, certified, and proven. Replacing it might not just cost money—it can cost time, compliance effort, and operational certainty.

That’s where GPIB’s continued relevance comes from: it’s still the interface sitting behind real equipment doing real work.

And the performance isn’t necessarily a deal-breaker for that world. GPIB is often described as capable of up to 8 MB/s, which isn’t going to impress anyone benchmarking SSDs—but is still perfectly adequate for many measurement and control tasks.

A modern Linux benefit: stability isn’t just convenience, it’s continuity

For the general public, “a stable driver” sounds like a small headline. For technical environments, it can mean the difference between:

- keeping a working test bench alive through OS upgrades, or

- freezing systems on older kernels because “upgrading breaks the setup.”

Once a driver is fully integrated in the main kernel, it’s more likely to be kept compatible as Linux evolves. That matters because the kernel changes constantly: internal interfaces shift, subsystems evolve, and what worked a few versions ago can subtly break if code isn’t actively maintained.

In practice, stable integration reduces the odds that GPIB users end up with a museum piece that only runs on a dusty PC in a corner.

The deeper story: open source has a long memory

There’s also something symbolic here.

A lot of modern software is built with short time horizons. Products ship, get replaced, lose support, and quietly disappear. Linux often runs in the opposite direction: if hardware still matters to someone—and if someone is willing to maintain the code—it can remain usable far beyond the expectations of commercial cycles.

This GPIB milestone is a reminder that the open-source ecosystem isn’t only about the newest hardware or the latest trend. It’s also about keeping useful tools alive, even if they’re older than many of the people writing the code today.

In a way, it’s a small victory for anyone who has ever dealt with aging equipment that still does its job perfectly—except the software world moved on and left it behind.

With Linux 6.19, GPIB isn’t being revived as nostalgia. It’s being recognized as what it still is: an interface that hasn’t finished its work.

FAQs

What is GPIB (HP-IB / IEEE-488) in simple terms?

It’s a communications interface created in 1972 to connect computers to laboratory instruments so they can be controlled and read automatically. It later became standardized as IEEE-488.

What does it mean that the GPIB driver moved out of “staging” in Linux 6.19?

It means the driver is no longer treated as a “work-in-progress” inside the kernel. It’s considered mature enough to live in the main kernel tree, with better expectations for stability and maintenance.

Who benefits from stable GPIB support in Linux today?

Labs, universities, calibration centers, engineers, and hobbyists who still run instruments or adapters that rely on GPIB—especially where replacing hardware is expensive or impractical.

Does this make old lab gear faster or more modern?

Not really. The big win is reliability and longevity: using older GPIB-based equipment on modern Linux systems without fragile patches or experimental driver status.