Most sysadmins know two main isolation tools by heart: containers and virtual machines. Containers are light but share the host kernel. VMs are heavier but bring their own kernel and better isolation.

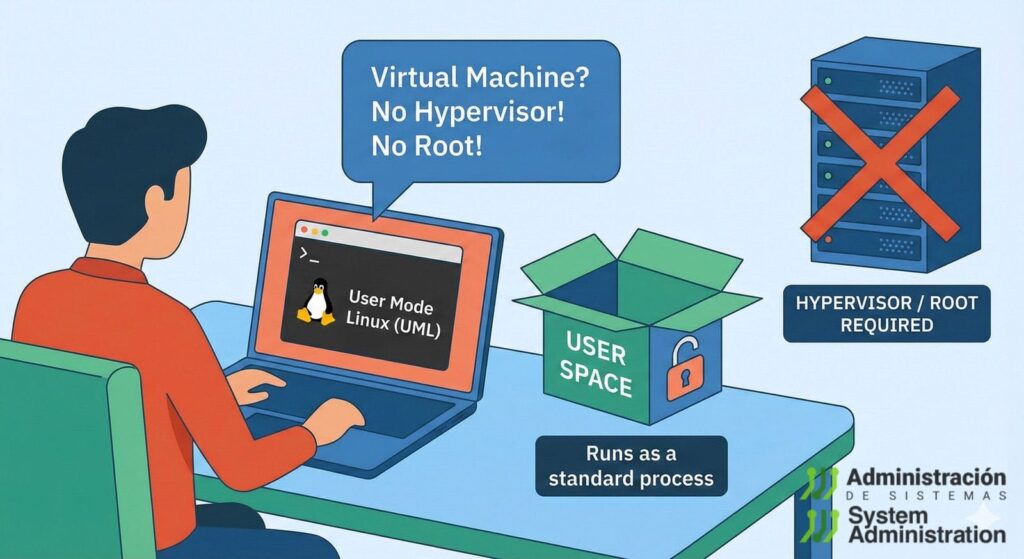

There’s a third option that sits somewhere in between and is still surprisingly useful in 2025, especially for low-risk experiments and kernel work: User Mode Linux (UML).

User Mode Linux lets you run a full Linux kernel as a user-space process on a Linux host. No KVM, no hardware virtualization, and—once the binaries are built—no root required to start the “VM”.

For sysadmins, that means:

- You can boot a real kernel in an environment that looks like a VM.

- You can test things without touching the host kernel or bootloader.

- You can run kernel experiments even on machines where you don’t control the hypervisor.

This article walks through what UML is, how it compares to the tools you already use, and how to get it running with a simple, repeatable example.

What User Mode Linux actually is

In short:

UML is a Linux kernel compiled to run on top of Linux, as a regular ELF executable.

You build it from mainline kernel sources with ARCH=um, and the result is a binary typically called linux. When you run that binary, it boots another Linux instance—complete with its own PID 1, process tree, virtual block devices, and login prompt.

Key ideas:

- The guest kernel runs in user space of the host kernel.

- Devices are paravirtualized:

- Console: mapped to the UML process’s stdin/stdout.

- Block devices: backed by files on the host via the

ubddriver. - Networking: uses host mechanisms (TUN/TAP, sockets, etc.).

- From the host’s point of view, it’s just another process tree (or a small set of processes).

You are not emulating a CPU and you’re not using hardware virtualization. The host kernel is still in full control, but the guest has its own view of the world.

UML vs containers vs “real” VMs

From a sysadmin’s perspective, the obvious question is: where does UML fit compared to containers and KVM-based VMs?

| Feature / Concern | Containers | User Mode Linux | KVM / QEMU VMs |

|---|---|---|---|

| Kernel | Shared with host | Separate UML kernel | Separate guest kernel |

| Needs hardware virtualization | No | No | Typically yes (KVM, etc.) |

| Runs as | Namespaced host processes | Regular user-space process | Userspace + hypervisor |

| Requires root to start VM | Typically yes | No (once binaries exist) | Usually yes |

| Isolation strength | Medium | Medium–high (but not a hard boundary) | High (with correct config) |

| Performance | Near host | Good, but with extra host/guest overhead | Best option for strong isolation |

| Best use cases | Apps, microservices | Experiments, kernel testing, CI sandboxes | Production VMs, strong isolation |

UML will not replace your virtualization platform. But for:

- Kernel experiments

- Training labs

- CI pipelines that need “a full Linux” but have no KVM

- Unprivileged sandboxes on shared servers

…it can be very handy.

Building a User Mode Linux kernel

You build UML from regular kernel sources; the only difference is the architecture target.

From your kernel source tree:

cd /path/to/linux

Configure for UML:

ARCH=um make menuconfig

On the first menu, you’ll see User Mode Linux specific options. For most sysadmin lab use cases you should enable at least:

- User-Mode Block Devices (UBD):

Lets the guest see host files as virtual disks. Look for the option described as:

“The User-Mode Linux port includes a driver called UBD which will let you access arbitrary files on the host computer as block devices.”

Make sure it’s set to Y.

Then build:

ARCH=um make -j"$(nproc)"

Code language: JavaScript (javascript)You’ll get a linux binary:

$ file linux

linux: ELF 64-bit LSB executable, x86-64, dynamically linked, ...

That linux file is your UML kernel.

Preparing a root filesystem

Like any Linux system, UML needs a root filesystem.

For a minimal lab environment, many admins use Buildroot to generate a tiny x86_64 rootfs image (e.g. ext2):

Assume you end up with:

/tmp/uml/rootfs.ext2

You can also reuse a small distro rootfs, or something like Alpine, as long as it’s compatible and packaged in a block image.

Adding a “data disk” as a file

To demonstrate how UML sees block devices and how changes persist, we’ll create a file-backed disk image on the host.

Create a 100 MiB file:

dd if=/dev/urandom of=./disk.ext4 bs=1M count=100

Code language: JavaScript (javascript)Format it with ext4:

sudo mkfs.ext4 ./disk.ext4

We’ll present this to the guest as a second disk using the ubd driver.

Booting UML with rootfs and data disk

Now run the UML kernel and map host files to guest block devices:

./linux \

ubd0=/tmp/uml/rootfs.ext2 \

ubd1=./disk.ext4 \

root=/dev/ubda

Code language: JavaScript (javascript)Explanation:

ubd0=/tmp/uml/rootfs.ext2→ appears as/dev/ubdain the guest.ubd1=./disk.ext4→ appears as/dev/ubdbin the guest.root=/dev/ubda→ tells the UML kernel which device to mount as/.

You’ll see a regular boot log, and then something like:

Welcome to Buildroot

buildroot login:

You now have:

- A full Linux kernel running as a user process.

- Its own PID 1 and process tree.

- Its own “disks” backed by host files.

All without touching KVM, libvirt, or your host bootloader.

Verifying persistence across guest and host

Inside the UML guest (typically log in as root):

Create a mount point:

# mkdir /mnt/disk

Code language: PHP (php)Mount the second disk:

# mount /dev/ubdb /mnt/disk

Code language: PHP (php)Write a test file:

# echo "This is a UML test!" > /mnt/disk/foo.txt

# cat /mnt/disk/foo.txt

This is a UML test!

Code language: PHP (php)Shut down the guest cleanly:

# poweroff

Code language: PHP (php)On the host, mount the same image:

sudo mkdir -p ./img

sudo mount ./disk.ext4 ./img

cat ./img/foo.txt

This is a UML test!

You’ve just:

- Booted a nested kernel.

- Mounted a file-backed disk inside it.

- Written data from the guest.

- Verified it from the host.

From a sysadmin viewpoint, that’s a very useful pattern for repeatable, disposable labs.

Why a sysadmin might actually care

UML is niche, but in a sysadmin toolbox, it’s good at a few things:

1. Safe kernel and low-level experiments

You can:

- Try new kernel configs.

- Experiment with filesystems and init systems.

- Reproduce panic scenarios or test patches.

If the UML kernel crashes, it only kills the process, not your host.

2. Labs and training without touching hypervisors

On shared infra where:

- You don’t control KVM.

- You can’t create VMs.

- You only get a user account on a Linux machine.

…you can still let people:

- Boot a kernel.

- See

/sbin/initstart. - Play with mount options, networking, and services.

All in an isolated environment that doesn’t require root.

3. CI environments without nested virtualization

Many CI environments don’t provide KVM, but you still want:

- “Real OS” tests (not just containers).

- Custom kernels or specific kernel features.

- Consistent, scriptable sandboxes.

UML can be started like any other binary:

./linux <args> </dev/null >/tmp/uml.log 2>&1 &

Code language: JavaScript (javascript)You can:

- Spin up multiple UML guests in parallel.

- Run regression suites against them.

- Destroy them by killing the process tree.

4. Debugging and observability experiments

Because UML runs as a regular process, you can attach:

strace,perf,gdb(for advanced kernel devs).- Cgroups and resource limits.

- Namespaces for additional isolation.

It gives you a lot of freedom to see what’s happening around and inside the nested kernel.

Limitations and things to watch out for

UML is useful, but it’s not magic. For sysadmins, these caveats matter:

Not a strong security boundary

- UML improves isolation over “just a chroot”, but:

- It still relies heavily on the host kernel.

- It’s not as hardened as a strictly configured hypervisor.

- Do not rely on UML alone for hostile multi-tenant isolation.

If you need real security barriers, stick to:

- Proper VM isolation (KVM, Xen, etc.).

- Strong kernel hardening and guest boundaries.

Architecture limitations

- UML targets x86/x86_64.

- It’s not a general replacement for ARM or other architectures.

- Good for lab hardware, workstations, and x86 servers.

Performance

- Every “device” operation maps to host syscalls and abstractions.

- For light to medium workloads and tests, it’s fine.

- For serious performance benchmarking or latency-sensitive services, use real VMs.

Networking configuration

Networking with UML is possible but not plug-and-play:

- You’ll likely use TUN/TAP, bridges, or NAT.

- It’s flexible, but needs manual setup or scripting.

For many test scenarios, a local rootfs without network is enough. For more advanced labs, you can invest the time to set up proper virtual networking.

Hardening and resource control

If you plan to let multiple users or CI jobs run UML:

- Use cgroups to cap:

- CPU

- Memory

- I/O

- Combine with Linux namespaces if you want to further isolate visible host resources.

- Monitor UML processes like any other service.

From the host perspective, UML is just another executable, which means you can apply your usual process policies.

When to reach for UML (and when not to)

Reach for UML when:

- You need a kernel sandbox without rebooting or touching the hypervisor.

- You’re teaching or learning low-level Linux concepts.

- You want reproducible test environments on machines without KVM.

- You want to experiment with kernel or init system behavior without risking a real VM or server.

Skip UML and use VMs/containers when:

- You’re running production workloads.

- You need strong isolation guarantees.

- Performance and latency really matter.

- You need non-x86 architectures.

User Mode Linux is not a modern buzzword technology. It quietly sits in the background, but for sysadmins who like to understand and control what’s happening under the hood, it offers something valuable: a full Linux kernel you can boot, break, and rebuild—just by running a process.

For labs, CI, and kernel-level tinkering, it’s still very much worth having in your toolkit.