For years, HTTP/3 has been sold as the next big leap for web performance: lower latency, fewer stalls, and a noticeably better experience on mobile networks. The theory is solid. The reality, however, can turn into an uncomfortable reminder of how fragile the Internet’s plumbing still is.

That’s exactly what a real-world engineering rollout story shows: after enabling HTTP/3 for a small slice of mobile traffic, their p99 latency dropped sharply and stayed down — about 40% lower for hours — especially for users stuck on poor LTE connections. But when they tried to scale that experiment, their CDN “stopped talking” to a significant chunk of users. The result was a volatile mix: spectacular wins for some, hard-to-diagnose failures for others.

Why HTTP/3 Can Be a Lifeline on Mobile

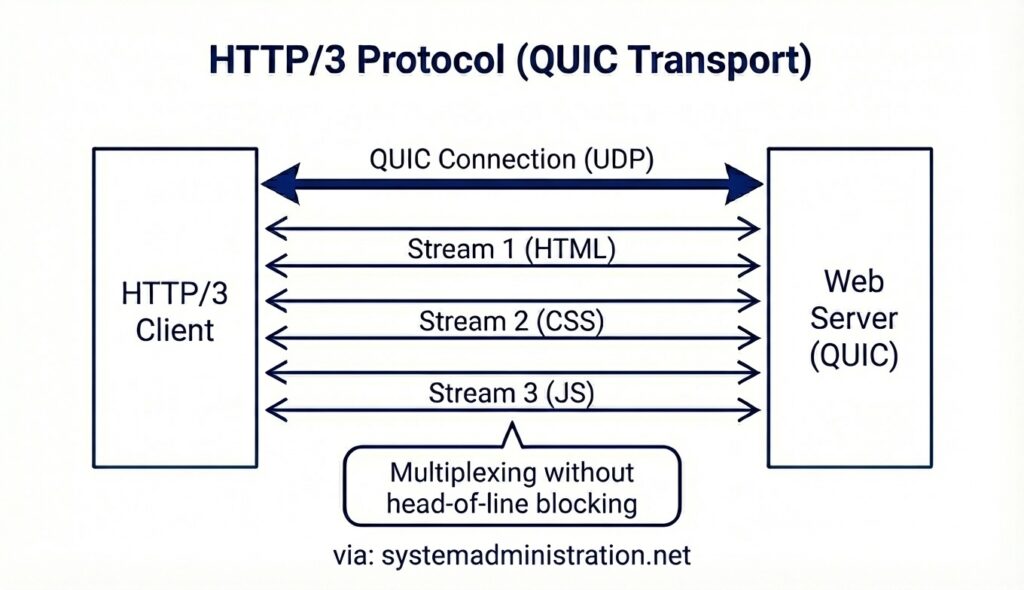

HTTP/3 runs over QUIC, a transport protocol designed to reduce classic TCP pain in environments with loss, jitter, and frequent network changes — all very common on mobile. QUIC was created specifically to limit head-of-line blocking effects and improve recovery from packet loss, among other goals. In high-latency or mobile-heavy scenarios, various analyses have found that HTTP/3 can deliver meaningful gains, though not always uniformly.

In the story shared, the API handles roughly 200 million requests per day, and around 60% come from mobile — phones on buses, in cafés, bouncing between towers. HTTP/2 over TCP was fine on decent Wi-Fi. On LTE with 2–5% packet loss, it was a different world: performance degraded fast and the long tail (p99) would spike. That’s precisely where QUIC/HTTP/3 is supposed to shine.

The Rollout: The 5% “Miracle” and the 50% Wake-Up Call

They started conservatively: HTTP/3 for 5% of mobile traffic. That’s where the shock landed — p99 dropped hard. Not a minor improvement, but the kind of change users feel immediately.

The trouble began when they pushed beyond that initial 5% toward more ambitious numbers. Two things stood out:

- The real-world ecosystem is full of broken paths. QUIC uses UDP, which means it runs into filtering, aggressive NAT behavior, middleboxes with strange quirks, and carrier or enterprise networks that simply don’t treat UDP like “normal” TCP traffic.

- Traditional observability doesn’t map cleanly. Many metrics that are straightforward with TCP (retransmits, handshake states, connection behavior) don’t translate neatly once you change transport. In their case, they ended up rewriting parts of their monitoring stack just to understand what was happening during the rollout.

This isn’t unusual. QUIC is relatively new in the IETF standards landscape, and the gap between “spec-compliant” and “operationally safe at scale” is still very real.

What Makes a CDN “Stop Talking” to Some Users?

Without pinning it on one single root cause (every network is different), several common failure modes match that symptom:

- UDP blocked or degraded in certain environments

QUIC rides on UDP. If a portion of networks filters UDP, rate-limits it, or handles it poorly, some clients can end up in timeouts, retries, or broken fallback behavior. - Discovery/advertising of HTTP/3 becomes a trap

Enabling HTTP/3 often involves discovery mechanisms (i.e., telling clients it’s available). If that’s done too aggressively or cached too long, some clients may keep trying a path that performs badly on their network and get stuck in a loop of poor connectivity. - Edge, load-balancing, and termination inconsistencies

Large CDNs aren’t perfectly uniform. If parts of the edge support HTTP/3 and other parts don’t — or internal routes aren’t fully ready — you can get intermittent failures that are painful to reproduce. - The modern web is inherently mixed

Even if the primary site supports HTTP/3, many resources come from third parties (analytics, ads, tags, image CDNs, etc.) that may stay on HTTP/2 or HTTP/1.1. That can dilute the benefit or create mixed behavior patterns.

Practical Takeaways from This Kind of Case

The lesson isn’t “HTTP/3 is dangerous.” It’s more uncomfortable than that: the Internet is still a patchwork of imperfect compatibility, and QUIC forces you to see those cracks up close.

- Roll out by segments, not just by percentage. Break down by country, carrier, ASN, or network type to quickly find where UDP/QUIC behaves badly.

- Instrument QUIC-specific telemetry. Don’t stop at “average latency.” Track handshake outcomes, retries, fallback rates, packet loss behavior, and client error patterns.

- Design (and test) fallback for the worst networks. The HTTP/2 path must be fast, clean, and loop-free.

- Be careful about how and when you advertise HTTP/3. In some deployments, discovery caching matters as much as support itself.

- Validate on real mobile networks. Lab environments don’t reproduce the nastiest realities of radio conditions, handovers, and congestion.

FAQ

Does HTTP/3 always make a website faster?

No. It tends to help most on mobile networks, high-latency links, or packet-loss-heavy conditions, and it may help less if many critical resources come from third parties that don’t support it.

Why can HTTP/3 fail on some networks?

Because it relies on UDP, which some networks block, throttle, or treat differently than TCP. QUIC also changes operational dynamics enough that you often need transport-aware monitoring to detect issues quickly.

Which metric is most useful to validate HTTP/3 in production?

Beyond averages, p99 latency is often the most revealing — it captures the “worst but common” user experience, especially on poor connections where HTTP/3 can make the biggest difference.

Is HTTP/3 worth enabling for a high-traffic mobile API?

Potentially yes, especially with lots of users on unstable networks — but only with segmented rollout, QUIC-aware telemetry, and a robust fallback plan to prevent silent degradations.

Sources:

- “RFC 9000 and its Siblings: An Overview of QUIC Standards” (Technical University of Munich, TUM)