Forty years ago, on 20 November 1985, Microsoft launched a modest graphical interface that would become a turning point in computing history: Windows 1.0. What began as a visual layer on top of austere MS-DOS went on to become the most widely used operating system on the planet, transforming primitive personal computers into tools that millions of non-technical users could understand and use. Four decades later, Windows remains a giant of the industry, proving that the right ideas, executed with persistence, can outlive almost every prediction.

From Command Line to Visual World: The Context That Made Windows Possible

To understand the impact of Windows, it’s necessary to go back to the mid-1980s. At that time, interacting with a personal computer required specialised knowledge. Users had to type complex commands on a black screen, memorise obscure syntax and understand computing logic that was far removed from the everyday experience of the general public. Computers were intimidating machines for specialists.

But as early as the 1960s, some visionaries had already imagined a different future. Douglas Engelbart, a researcher at the Stanford Research Institute, proposed a revolutionary concept: a system based on windows, icons and control through a pointing device he called a mouse. On 9 December 1968, Engelbart gave a legendary demonstration that would later be known as “The Mother of All Demos”, inspiring an entire generation of innovators.

Years later, Apple turned many of these ideas into a commercial product with the Macintosh, launched in 1984, which brought a full graphical user interface to market. However, the Macintosh was an expensive machine, within reach only of those with significant purchasing power. Microsoft, watching the success of the concept but aware of the price gap, decided to bring the graphical interface to IBM PC-compatible machines, which were much cheaper and already had a large software ecosystem. Out of that strategic calculation, Windows was born.

The First Window: Modest Beginnings of a Major Transformation

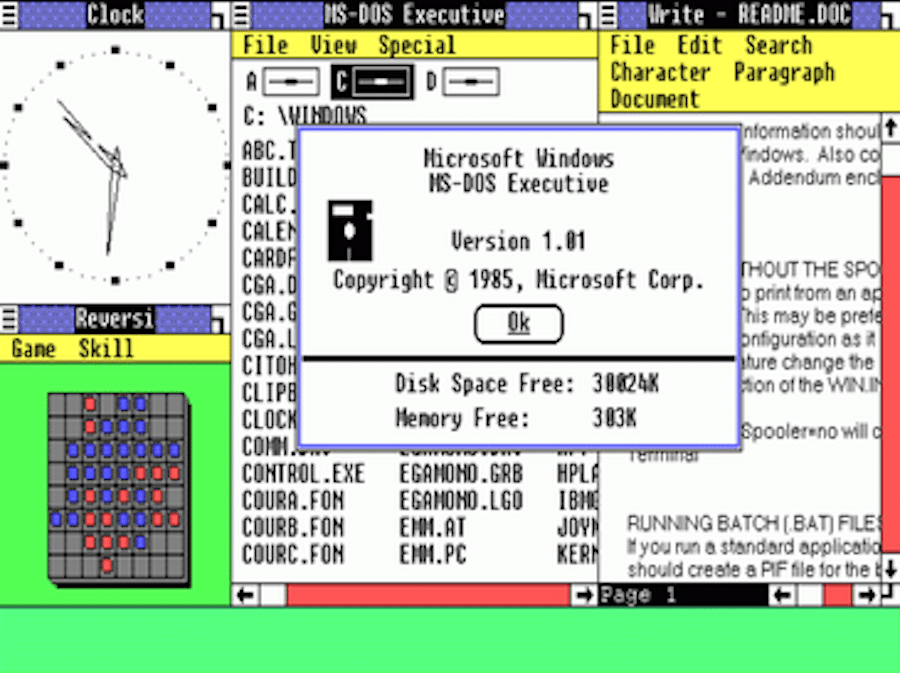

From a technical standpoint, Windows 1.0 was quite primitive. It was not a complete operating system, but a visual layer running on top of MS-DOS. At its core was a 16-bit command interpreter called MS-DOS Executive, which sat above DOS and allowed programs to run inside windows.

The product launched at around 99 US dollars, a substantial amount in 1985 in terms of purchasing power.

The interface had quirks that would be unacceptable today. Windows could not freely overlap; instead, they were arranged in a strict tiled layout. The mouse was the primary control device, but menus behaved in a way that felt unintuitive: users had to keep the mouse button pressed for the options to remain visible. These limitations reflected both the constraints of the hardware of the time and the lack of precedents for a mass-market graphical interface.

The hardware requirements for running Windows 1.0 were also demanding for that era. Users needed an Intel 8086 or 8088 processor, at least 256 kilobytes of RAM, a graphics adapter and two double-sided floppy drives or a hard drive. Many machines struggled to run several applications at once, especially if they did not have the 512 kilobytes of RAM Microsoft recommended. For comparison, Windows 11 currently requires a minimum of 4 gigabytes of RAM, which says a lot about how far hardware has come in four decades.

Early Built-In Apps That Pointed to the Future

Despite its technical limitations, Windows 1.0 shipped with a set of applications that clearly showed the potential of the concept.

- Paintbrush, the direct ancestor of today’s Paint, allowed users to create simple drawings.

- Notepad and Write offered basic text editing.

- A Calculator handled everyday maths.

- A Clock, a terminal, Cardfile (a card-based mini database), a clipboard manager and a print spooler completed the bundle.

By today’s standards these tools were rudimentary, but together they outlined a coherent vision of how a personal computer could serve the everyday needs of non-technical users.

What’s striking is how many of those ideas survived. Paint is still part of Windows. Notepad, though much improved, remains essentially what it was: a fast, minimal text editor. This continuity suggests that Microsoft identified very early on which tools were truly fundamental for users.

A Lukewarm Market Reception and the Power of Persistence

The initial reception of Windows 1.0 was mixed at best. Reviewers criticised its sluggish performance, especially when multiple applications were open. Compatibility with existing DOS software was limited, and there were very few programs written specifically for Windows. Compared to Apple’s Macintosh, which had arrived a year earlier with a more polished graphical environment, Windows looked technically inferior.

Some contemporary analysts used colourful language to describe the experience, comparing running Windows on a PC with 512 kilobytes of RAM to “molasses poured in the Arctic” – an image that captured the frustration caused by its slow performance.

The key difference for Microsoft, however, was attitude. Rather than abandoning the idea under criticism, the company kept iterating. It released several updates to the 1.x line, improved hardware support and added better keyboard layouts for European markets. The real turning point arrived with Windows 2.0 and, above all, Windows 3.0, launched in 1990.

Windows 3.0 represented a qualitative leap over its predecessors. It brought a much more refined graphical interface, significantly improved performance and arrived at exactly the right moment: hardware prices had fallen, personal computers were becoming mainstream and businesses were ready to standardise on a graphical environment. What seemed like an experiment in 1985 became, just five years later, the foundation of a new industry standard.

Building the Ecosystem: How Windows Conquered Home and Office

Windows’ dominance wasn’t due solely to its interface. Its success was built on a powerful combination: a strategic ecosystem and an open hardware platform.

The IBM PC architecture, adopted and cloned by dozens of manufacturers, created a vast market of compatible machines at ever lower prices. While Apple kept tight control over its hardware, the PC universe exploded in variety and volume. Windows was perfectly positioned to ride that wave: it could run on hardware from countless vendors, making it far more accessible.

At the same time, third-party software development took off. Throughout the 1990s, software companies realised that the Windows market offered huge business opportunities. The catalogue of applications expanded at an extraordinary pace:

- Office suites

- Graphic design and publishing tools

- Databases and line-of-business applications

- Development environments

- Specialised programs for almost every sector

This network effect was decisive. The more software there was for Windows, the more attractive the platform became for users and businesses – and the more incentive developers had to keep building for it.

Enterprises, meanwhile, saw in Windows a way to modernise their IT at lower cost than with proprietary alternatives. The combination of relatively inexpensive hardware, a huge talent pool of Windows developers and broad support for industry standards made it the most pragmatic choice. In a few short years, Windows became the default platform both in the office and at home.

Forty Years of Continuous Evolution

From Windows 1.0 to Windows 11, the operating system has been transformed. Later versions added capabilities that would have seemed like science fiction in 1985: true multitasking, built-in networking, the web, high-quality multimedia, hardware-accelerated graphics, virtualisation, advanced security models, cloud integration and even AI-powered features.

Windows is no longer a thin visual layer on DOS; it’s a fully fledged, complex operating system running on everything from lightweight laptops to powerful workstations and servers in data centres.

And yet, the core idea is still recognisable. Windows remains faithful to Engelbart’s original vision: a visual interface of windows and icons controlled by a pointing device. The Windows 11 desktop, with its taskbar, start menu, windows and context menus, is a direct descendant of that tiled desktop from 1985, even if the aesthetics and underlying technology have changed completely.

Windows’ Legacy in Computing History

This 40th anniversary is an opportunity to reflect on the long-term impact of Windows. It wasn’t necessarily the most elegant or technically pure system — many would argue that Unix and its derivatives are superior in modularity and flexibility — but Windows was the right solution for the right moment. It brought personal computing within reach of millions of people who would never have learned a command line.

Today, Windows 1.0 is a digital relic. Enthusiasts can run it in emulators or virtual machines for nostalgia. From time to time, Microsoft itself nods to its history with retro-themed projects, such as the playful Windows 1.11 experience inspired by the series Stranger Things, recreating the look and feel of the 1980s for fun.

But the real legacy of Windows isn’t in retro demos. It’s in the fact that, forty years after that first release, Windows is still the dominant desktop operating system and is still evolving. In an industry where products can rise and fall in a few years, this kind of longevity is exceptional.

A Final Reflection: The Persistence of Good Ideas

The 40th anniversary of Windows is a reminder that technological progress doesn’t always reward the inventor of an idea, but often the company that knows how to industrialise, adapt and scale it.

Douglas Engelbart imagined the mouse and the graphical interface; Xerox PARC pioneered many of the concepts; Apple turned them into a polished, integrated product. Microsoft, for its part, understood how to bring that vision to the mass market, riding the wave of the PC explosion and building a software ecosystem around it.

The story also shows that successful innovation is rarely a single brilliant product, but rather a sequence of incremental improvements. Windows 1.0 was limited, but it made Windows 2.0 possible. Windows 2.0 was better, but it was Windows 3.0 that truly conquered the market. Each generation learned from the previous one and moved a little closer to what users needed.

In an era when many companies chase instant disruption, the long life of Windows offers a different lesson: sometimes the winning strategy is to evolve constantly, listen to users and stay committed to a core vision even when the first steps are rough. Forty years on, Windows is still proof that this approach can work.

FAQ: 40 Years of Windows

When was Windows 1.0 released, and what were its minimum hardware requirements?

Windows 1.0 was officially released on 20 November 1985 in the United States. To run it, users needed an Intel 8086 or 8088 CPU, at least 256 KB of RAM (512 KB recommended for reasonable performance), a graphics adapter and two double-sided floppy drives or a hard drive. The launch price was around 99 US dollars, a significant amount at the time.

If Windows 1.0 was so innovative, why was its initial market reception so lukewarm?

Windows 1.0 did bring the graphical interface to the IBM PC, but it suffered from poor performance, limited compatibility with existing DOS applications and a very small catalogue of native Windows software. Compared with Apple’s Macintosh, which was more mature as a graphical system, Windows looked slow and rough around the edges. Even so, Microsoft kept improving it and, with Windows 2.x and especially Windows 3.0, managed to turn that early experiment into a mass-market success.

Which applications were included with Windows 1.0, and do any of them still exist today?

Windows 1.0 included Paintbrush (the precursor to Paint), Notepad, Write, Calculator, a clock, a terminal, Cardfile, a clipboard manager and a print spooler. Several of these utilities — notably Paint and Notepad — are still shipped with modern versions of Windows, although greatly improved, which shows how accurate Microsoft was in identifying the core tools users needed.

What changed between Windows 1.0 and Windows 3.0 that allowed Windows to finally dominate the market?

By the time Windows 3.0 arrived in 1990, several factors had aligned:

- The user interface was more polished and easier to use.

- Performance and memory management had improved significantly.

- PC hardware had become much more powerful and affordable, making graphical environments practical.

- A large ecosystem of third-party applications was now available for Windows.

This combination of better software, cheaper and faster hardware and a booming application ecosystem turned Windows from a curiosity into the de facto standard for personal and business computing.