IP addresses are everywhere, yet they rarely get much attention. Routers are configured, virtual machines are deployed, VPN tunnels are set up – and there are those silent blocks of numbers that, when understood properly, save you from a lot of headaches.

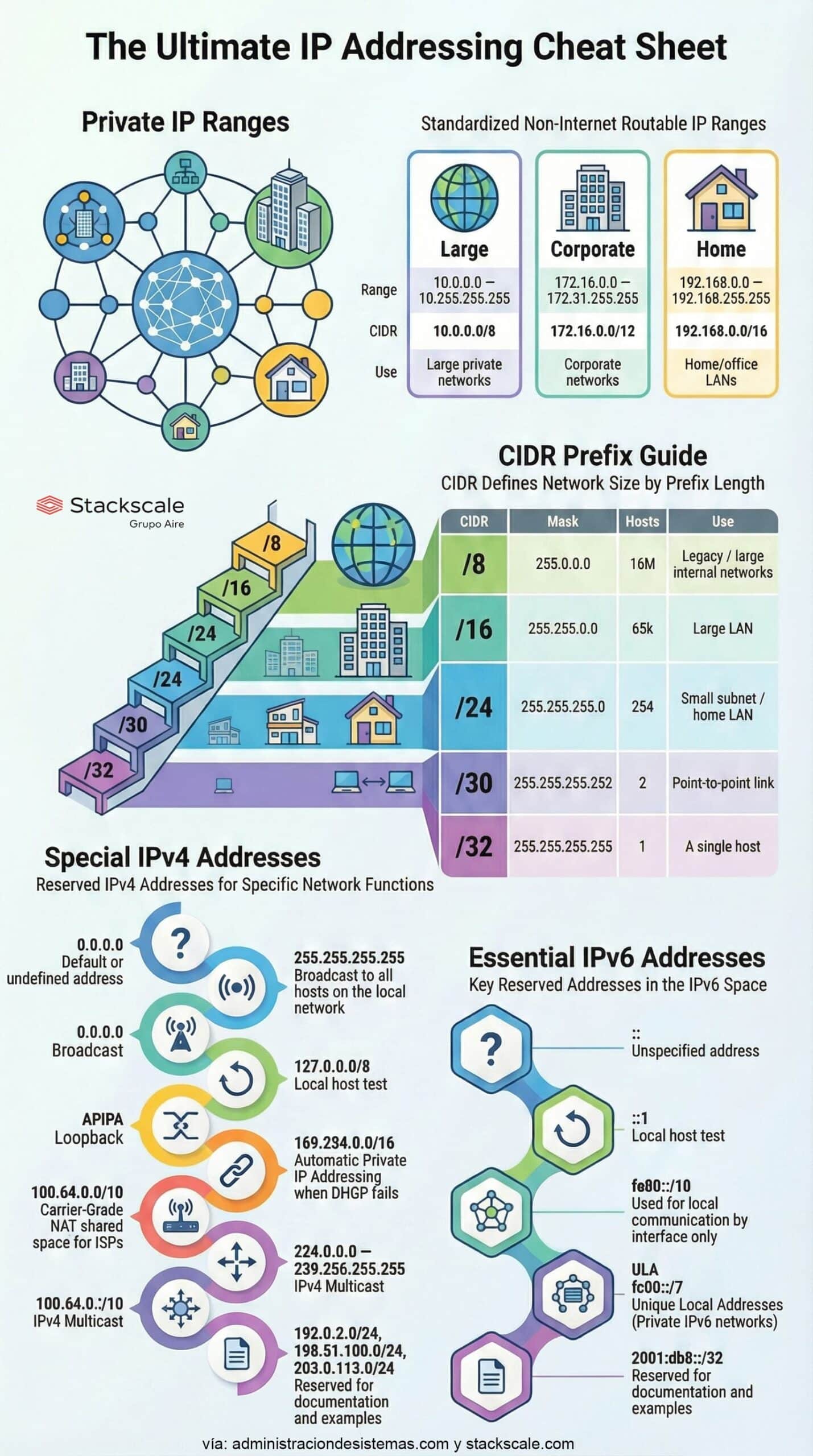

Behind an IP there’s far more than “four octets”. There are strict rules that decide whether an address can reach the public Internet, how many devices fit in a network, which IP is used for testing, or which one points to a single host. The cheat sheet that goes with this article condenses those ideas visually; here we dig into the concepts behind it.

1. Not Every IP Can Reach the Internet: the Private Network Club

The first thing to remember is that not every IP address is routable on the Internet. A big chunk of the IPv4 space is reserved for private networks – the ones you use at home, in the office, or in corporate environments.

The three classic private blocks are:

- 10.0.0.0/8

Range: 10.0.0.0 – 10.255.255.255

Typical use: large private networks and heavily segmented environments. - 172.16.0.0/12

Range: 172.16.0.0 – 172.31.255.255

Typical use: corporate networks and data centers with many subnets. - 192.168.0.0/16

Range: 192.168.0.0 – 192.168.255.255

Typical use: home and small office LANs (the classic 192.168.1.x from your router).

These ranges are not advertised on the public Internet. A packet sourced from 192.168.x.x should never be seen beyond the router; it’s translated via NAT to a public IP before going out.

Thanks to this design, millions of homes and companies can reuse the same private addresses without colliding with each other, stretching IPv4’s lifetime and enabling complex internal architectures with a limited global address space.

2. The “/” Prefix Rules Everything: How CIDR Decides How Many Devices Fit

That number after the slash —/8, /16, /24…— isn’t decorative. It’s the CIDR prefix, and it defines the exact size of the network.

In practice, the prefix is another way of writing the subnet mask:

- /8 → 255.0.0.0

- /16 → 255.255.0.0

- /24 → 255.255.255.0

The cheat sheet shows how dramatic a small change can be:

| Prefix | Mask | Approx. usable hosts | Typical use |

|---|---|---|---|

| /8 | 255.0.0.0 | ~16 million | Legacy / very large internal networks |

| /16 | 255.255.0.0 | ~65,000 | Large LANs / corporate networks |

| /24 | 255.255.255.0 | 254 | Home or small office subnet |

| /30 | 255.255.255.252 | 2 | Point-to-point link |

| /32 | 255.255.255.255 | 1 | A single host |

What’s counterintuitive is how sensitive everything is to a single number:

- A /24 gives you 254 hosts – perfect for a user VLAN.

- A /23 (just one bit less) almost doubles the number of available addresses.

- A /8 is a monster, meant for legacy or heavily segmented environments.

Understanding this bit game is key to clean subnetting: not running out of addresses, but also not wasting huge blocks you’ll later miss somewhere else.

3. “Ghost” Addresses with No Host – but Critical for Networking

Not every IPv4 address points to a specific device. Some have special roles and are essential for diagnostics, testing, or core network functions.

Some of the most important ones:

- Loopback – 127.0.0.0/8

The best-known one is 127.0.0.1. It lets a machine “talk to itself”. It’s used constantly to test services, sockets, and applications without ever leaving the host. - Broadcast – 255.255.255.255

Think of this as the network’s megaphone. Any packet sent to this address is received by all devices on the local subnet. Many discovery and announcement protocols rely on it. - APIPA – 169.254.0.0/16

Range a machine assigns to itself when DHCP fails. If an interface shows an IP starting with 169.254, it’s a very clear sign something’s wrong with address assignment on that network. - CGNAT – 100.64.0.0/10

Reserved space for ISPs to perform large-scale NAT, hiding many customers behind a few public IPs. Very common in mobile networks and some residential connections. - Multicast – 224.0.0.0 – 239.255.255.255

Used to send traffic to multiple receivers at once (streaming, routing protocols, discovery services) without replicating packets one by one as in unicast.

The cheat sheet also includes ranges like 192.0.2.0/24, 198.51.100.0/24 or 203.0.113.0/24, reserved for documentation and examples. They exist precisely to avoid confusion with real networks.

Knowing these “special” addresses saves a lot of time when staring at tcpdump output or logs: whenever one of them appears, it’s telling you something specific about what’s happening on the network.

4. The Smallest Network That Makes Sense… and Why a /30 Only Fits Two Devices

In the prefix table there’s one value that always catches the eye: /30. It’s the smallest useful IPv4 subnet when you want a traditional layer-3 link.

A /30 block has 4 addresses in total:

- 1 for the network ID.

- 1 for the broadcast.

- 2 usable addresses for hosts.

What’s the point of something so tiny? It’s perfect for point-to-point links between routers:

- Router A: first usable IP.

- Router B: second usable IP.

That’s it. There’s no need to burn a full /24 just to connect two devices. A /30 lets you use the address space extremely efficiently – which matters a lot in large networks where every block counts.

If you go one step further you reach /32, which identifies a single host. It’s used for things like static routes to an exact IP, very granular firewall rules, or virtual addresses assigned to services.

5. IPv6 Has Its Own “Magic” Addresses Too

Although the cheat sheet focuses mainly on IPv4, it also includes a very handy summary of reserved IPv6 addresses worth remembering:

::– Unspecified address.::1– IPv6 loopback (the equivalent of 127.0.0.1).fe80::/10– Link-local addresses, only valid on the local network segment.fc00::/7– ULA (Unique Local Addresses), the IPv6 equivalent of private networks.2001:db8::/32– Reserved for documentation and examples.

In IPv6 the address space is enormous, but the core ideas stay the same: ranges for internal networks, for testing, for local communication… all driven by the same prefix and mask logic, just with 128 bits instead of 32.

Much More Than Numbers: a Mental Map So You Don’t Get Lost

IP addresses are not random sequences: they’re a design language that describes how a network is laid out.

- Private ranges draw the line between internal and public space.

- CIDR prefixes decide how many devices fit into each segment.

- Special addresses let you test, announce, diagnose, or group traffic.

- And tiny subnets like /30 remind you just how finely you can slice the address space.

Keeping a cheat sheet like this infographic close by —printed on the wall of the data center or open on your desktop— won’t replace real knowledge, but it will help you turn theory into something immediate and visual. Next time you see a “weird” IP in a log or you have to design a new VLAN, these small secrets will make everything click into place.