Every time someone opens a website, their browser starts “talking” about them. No cookie banners, no login, no clicking “Allow” on camera or microphone permissions. Just by loading a page, the browser sends a surprising amount of technical details that, when combined, are enough to single out one device among billions.

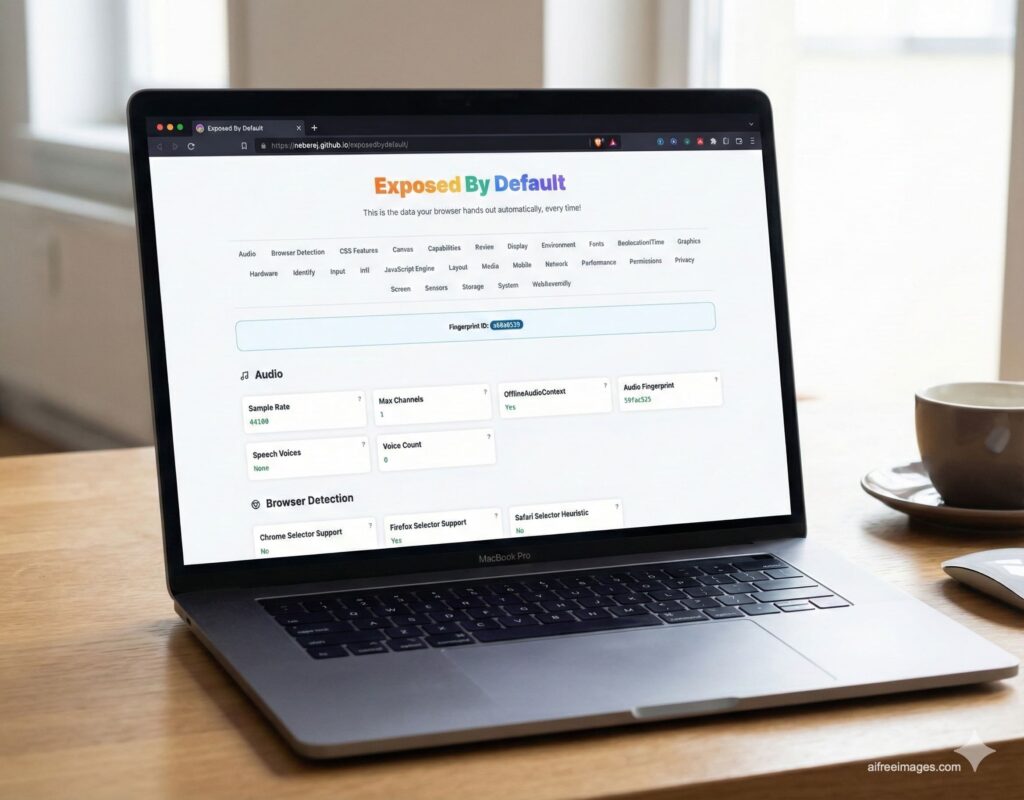

The project Exposed by Default, published in late November 2025 as an open-source demo on GitHub, turns this invisible process into something you can actually see. The page runs locally in your browser and lists, in real time, everything it can infer about your setup. Then it condenses that data into a unique “fingerprint ID”, effectively placing your device as “1 in more than 17,179 million” possible configurations.

Crucially, the site doesn’t upload anything to a server or store profiles. It simply shows what any ordinary web page could collect silently behind the scenes—only this time it’s visible.

Beyond cookies: a technical fingerprint that’s hard to hide

For years, online privacy has been framed mainly around cookies, tracking pixels, and IP addresses. But modern browser fingerprinting goes far beyond that. Tools like Exposed by Default show that a browser reveals dozens of parameters that, taken together, work like a highly accurate digital fingerprint.

Among the types of data exposed are:

- Audio characteristics: sampling rate, available channels, supported audio paths.

- Canvas fingerprints: subtle differences in how graphics are rendered on the HTML canvas reveal details about your GPU, drivers, and graphics stack.

- Advanced APIs: support for interfaces like

AudioDecoder,WebCodecs, or WebGPU says a lot about your browser version and capabilities. - Hardware hints: CPU architecture (ARM vs x86_64), approximate core count, rough memory size, and sometimes GPU details.

- Display information: screen resolution, available viewport, pixel density, and aspect ratio.

- Installed fonts and metrics: the exact font set, and how each font measures, is one of the oldest and strongest signals to distinguish machines.

- Locale and regional settings: language (for example,

es-ES), time zone (Europe/Madrid), number formats (1,234,567.89vs1.234.567,89), and date formats. - Media capabilities: supported codecs such as AV1, HEVC, VP9, and their constraints.

- JavaScript engine quirks: tiny timing differences and math results that vary by platform and engine version.

- Input devices: mouse, touch screen, stylus, gamepad, or combinations of them.

- Floating-point precision: how the browser handles specific numeric edge cases, which can differ by CPU and JS engine.

- Scrollbar characteristics: width, style, and behavior—small details that vary between OSes and themes.

- Permission states: whether camera, microphone, notifications, and sensors are blocked, allowed, or in “prompt” state.

- Storage capabilities: support for cookies, localStorage, sessionStorage, IndexedDB, Service Workers, and more.

None of these values, on their own, looks particularly sensitive. But stitched together, they form a high-dimensional vector that is extremely unlikely to match another random device. That’s the core of fingerprinting: combining “boring” technical details into something uniquely identifying.

It works even without cookies — and often in private mode

The key advantage of fingerprinting over cookies is that it doesn’t rely on local storage. Clearing cookies, wiping history, or opening a private/incognito window does not stop the browser from exposing most of these characteristics every time it renders a page.

In the real world, commercial libraries such as FingerprintJS or in-house anti-fraud SDKs have been using this approach for years. They measure dozens or hundreds of attributes and hash them into an identifier that remains stable across sessions. Even if the user periodically “cleans up” their browser, the underlying fingerprint often stays similar enough to be linked.

Researchers now consider fingerprinting one of the most persistent tracking mechanisms on the modern web. Recent work has highlighted even more advanced variants—like code that uses WebAssembly to hide how the fingerprint is generated, making it harder for defenses to detect and block.

“Exposed by Default”: a mirror of what’s happening in the background

The Exposed by Default project was built precisely to make this invisible layer tangible. The site loads as a normal webpage, runs its detection logic entirely on the client, and shows the results in a clean interface. Because the code is open-source, anyone can inspect how each signal is collected and what the browser is actually revealing.

Recent updates to the repository have added extra checks, such as:

- detection of available text-to-speech voices, and

- simple ad-blocker detection,

both of which add yet more granularity to a device’s fingerprint.

The point is not to track visitors, but to raise awareness. It’s one thing to read abstractly that “your browser leaks information”; it’s very different to see, line by line, how your system locale, fonts, audio stack, GPU behavior, and scrollbar width combine into a seemingly unique ID.

Why browsers can’t just “turn it all off”

If this is such a problem, why don’t browser vendors simply block all these data points? The answer lies in the constant trade-off between functionality and privacy.

Most of the APIs used in fingerprinting exist for legitimate reasons:

- Canvas and WebGL power online games, design tools, and rich visualizations.

- Media APIs enable video conferencing, streaming, and local processing of audio and video.

- Locale and font details improve accessibility and allow websites to render correctly across platforms.

If browsers were to shut down all these channels, half the modern web would break.

Instead, major vendors have taken a more incremental approach:

– reducing precision (for example, rounding timings),

– adding noise to some measurements,

– standardizing locale exposure, and

– grouping devices into broad “buckets” rather than exposing fine-grained differences.

On top of that, privacy-focused tools add extra layers. Extensions like JShelter, and hardened browsers such as Tor Browser, Mullvad Browser, or Brave in strict mode, intercept or spoof many fingerprint-relevant APIs. Academic evaluations, however, show that only the most aggressive setups (notably Tor) offer strong resistance against state-of-the-art fingerprinting; mainstream browsers remain at least partially trackable.

What regular users can realistically do

There’s no magic switch to make fingerprinting disappear, but there are ways to limit it and make tracking harder:

- Choose browsers with strong anti-fingerprinting defenses

Tor Browser and Mullvad Browser try to make all users look as similar as possible. They standardize many parameters and block or fake risky APIs, so trackers see a relatively uniform crowd instead of millions of unique setups. - Use privacy extensions wisely

Script blockers, ad blockers, and tools like JShelter can reduce the number of APIs accessible to websites and fuzz some of the data they see. Combined with a good content blocker, this already cuts down many mainstream tracking scripts. - Avoid unnecessary customization

Exotic fonts, unusual themes, rare plugins, and long lists of extensions all make a device stand out. Sticking closer to a “default-ish” setup, at least in one of your browsers, helps you blend in with a larger pool of users. - Separate profiles and contexts

Using different browsers or profiles for banking, work, and general browsing makes it harder for a single fingerprint to span every aspect of your online life. Compartmentalization won’t remove fingerprinting, but it limits how much a single profile can reveal. - Lock down permissions and APIs

Deny camera, microphone, sensors, and notifications by default, and only grant them when absolutely needed. Combined with strict autoplay and third-party cookie policies, this reduces both attack surface and data leakage.

What Exposed by Default makes clear is that, even with precautions, a browser still “talks” a lot more than most people realize. Understanding that reality is the first step toward demanding better defaults from vendors and more responsible data practices from websites and advertisers.

FAQ: Browser fingerprinting and “Exposed by Default”

How can a website identify my device without cookies or logging in?

By using browser fingerprinting. The site runs JavaScript that queries dozens of APIs—Canvas, WebGL, audio, fonts, screen, locale, and more—and turns those values into a hash. That hash works as a persistent ID that often remains similar even if you clear cookies or switch to private mode.

Is there a way to see what my browser is leaking right now?

Yes. Projects like Exposed by Default show, in real time, which attributes your browser exposes and how they combine into a fingerprint. In that demo, all processing happens locally, and no data is sent or stored, so you can safely use it as a “mirror” of your browser’s behavior.

Which browsers are best at resisting fingerprinting?

Research consistently finds that Tor Browser (and, to a lesser extent, Mullvad Browser) offers the strongest protection, because they enforce strict uniformity across users and disable or spoof many fingerprint-heavy features. Other browsers like Brave and Firefox have added partial protections, but advanced trackers can still distinguish users with a high degree of accuracy.

If I’m not a high-risk target, should I really care?

For most people, fingerprinting is used mainly for advertising, analytics, and fraud detection. But the same techniques can be applied to more sensitive profiling—for example, tracking dissidents, journalists, or specific corporate targets. Even if you don’t fall into those categories, being aware of what your browser reveals puts you in a better position to choose tools and settings that align with your own privacy comfort level.