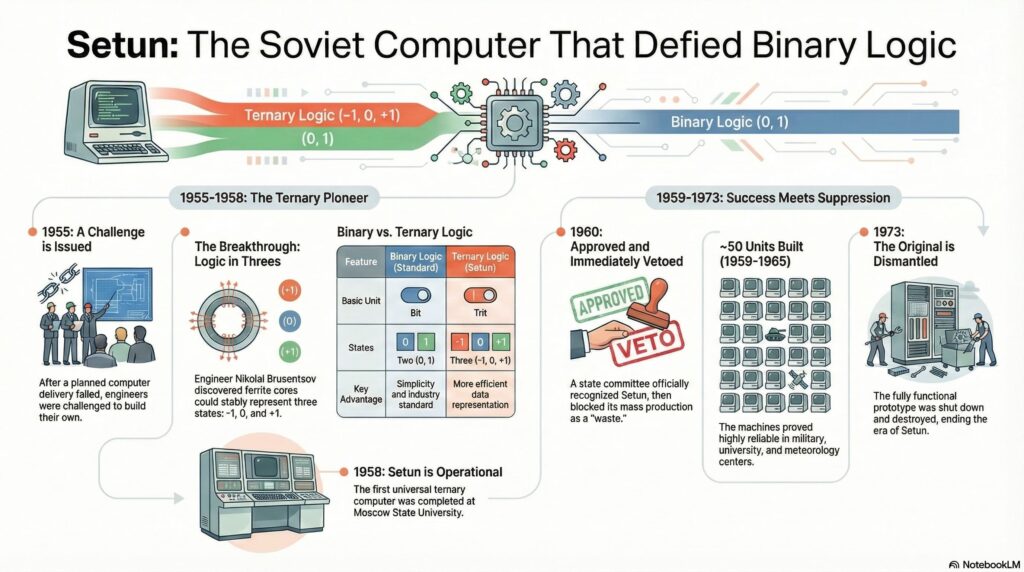

In the late 1950s, while almost the entire computing world was standardizing around binary logic, a small team at Moscow State University built something radically different: a universal computer based on three states instead of two. That system was called Setun, and from a systems and infrastructure perspective it is a fascinating anomaly: elegant design, harsh hardware constraints, good “observability” for its time, and reliability that surprised even its official evaluators.

Setun’s story is not just about an unusual architecture. It is also the story of a technically solid platform suffocated by politics, industrial agendas, and bureaucracy. And it still carries uncomfortable lessons for anyone managing large-scale systems in highly standardized environments today.

A university project that started with “no machine? Then we’ll build one”

The origin of Setun begins with a logistical failure. In the mid-1950s, Moscow State University had been promised an M-2 computer, ordered by mathematician Sergei Sobolev for a new computing center. The room was ready, the engineering team was in place – but an academic and personal dispute between Sobolev and the lab that owned the M-2 blocked the transfer. The machine never arrived.

Faced with that fiasco, Sobolev changed strategy. If there was no available hardware, they would build their own. His brief will sound familiar to any modern IT leader: he wanted a cheap, robust, easy-to-learn machine that could be deployed across universities and research institutes.

The technical design fell to a young engineer, Nikolai Brusentsov. He later recalled that they couldn’t realistically rely on vacuum tubes, and semiconductors were still scarce; the only practical option was to use ferrite elements, both for logic and memory. While experimenting with these magnetic cores, he noticed something striking: with the right wiring, they could be driven in three stable states, not just two.

That practical observation opened the door to something very unorthodox: a computer that wouldn’t think in bits, but in trits.

Balanced ternary logic: when sign comes built in

On top of that physical behavior, the team built the machine around balanced ternary logic. Instead of just 0 and 1, each information unit could take three values: −1, 0, or +1.

That number system has several implications that low-level programmers and system architects today can appreciate:

- Numbers have an implicit sign: the most significant trit tells you whether the value is positive or negative.

- There is no need to distinguish between “signed” and “unsigned” integers as in binary systems.

- Rounding around zero becomes more natural, because the representation is symmetric.

Logically, Setun implemented a three-valued logic (false, unknown, true), very much in line with the system developed by Polish logician Jan Łukasiewicz. With three basic operations — negation, conjunction and disjunction — you can build ternary circuits that perform addition, subtraction and other arithmetic operations.

Brusentsov and his colleagues validated this in hardware. Even though a trit was somewhat more complex to implement than a bit at circuit level, the overall architecture became more compact and conceptually clean. Local complexity was offset by a global simplicity in number handling and machine design.

Setun’s architecture from a systems point of view

Seen through the eyes of a systems engineer, Setun’s architecture was surprisingly structured for its era. The machine was divided into six functional units:

- Arithmetic Logic Unit (ALU), handling trit-based operations, including integer and floating-point arithmetic.

- Control Unit, orchestrating execution of ternary instructions.

- Operational memory, with two clearly separated tiers.

- Input unit, a five-position paper tape reader running at about 800 characters per second.

- Output unit, also based on physical media.

- Secondary memory, a magnetic drum.

The main memory combined:

- A fast ferrite-core random-access block with 162 words of 9 trits.

- A magnetic drum with 1,944 words, much slower but offering higher capacity.

In practice, for an operator or systems administrator at the time, the ferrite block behaved like a low-latency cache in front of the drum. Data came in serially from paper tape, was loaded into a 9-trit shift register for serial-to-parallel conversion, and from there could be stored either in fast RAM or on the drum depending on program logic.

The instruction set comprised 24 operations, 21 of which were used in normal programming. Setun supported conditional and unconditional jumps, additions and subtractions in around 180 microseconds, and multiplications in roughly 320 microseconds. It wasn’t the fastest machine on paper compared with large Western or Soviet mainframes, but top speed was not the primary design goal. In real deployments, availability and robustness mattered more than peak performance.

One detail that often comes up in modern analyses is the hybrid implementation of the magnetic drum. There, ternary states were encoded onto combinations of two binary bits. On paper this might look wasteful, but later work showed that this mapping could even deliver performance benefits for some arithmetic patterns, while the core logic and ferrite RAM still worked directly with genuine ternary states.

Uptime, harsh climates and integration mistakes: the “ops” side of Setun

Where Setun truly stood out was in precisely the area that keeps sysadmins awake at night: uptime in production.

In April 1960, an interdepartmental commission subjected the machine to three weeks of continuous testing at Moscow State University’s computing center. The conclusion was unambiguous: Setun met its specifications and ran without failures throughout the entire test period.

Despite the political obstacles that would follow, between 1959 and 1965 about 50 units were manufactured and deployed across the Soviet Union. Those machines ran in very different environments:

- Military aviation academies, where Setun was integrated into automated test systems for aircraft engines.

- Hydrometeorological centers, generating short-term weather forecasts.

- University departments of chemistry and mathematics, used for numerical work and teaching.

This happened without anything resembling today’s vendor support contracts, spare part logistics or 24/7 SLAs. Brusentsov liked to emphasize that Setun ran for years without on-site service and almost no replacement parts, operating both in arid climates such as Ashgabat and in the extreme winters of Yakutsk.

Still, the system wasn’t immune to the kind of “optimization” that any modern admin will recognize. In one production model, a fan that should have drawn air out of the drum chamber was relocated “for ease of mounting”. Outwardly, everything looked neat; internally, the airflow was now directed along the floor, leaving the upper parts of the cabinet with temperatures more than twice the permitted limit. It’s a textbook example of how a minor mechanical change, made without regard for the original design, can severely degrade thermal behavior and hence long-term reliability.

Standards, internal politics and the closing of the ternary path

Despite its technical merits, Setun collided head-on with the Soviet Union’s technology strategy.

In 1959, the machine was shown at the USSR’s Exhibition of Economic Achievements and discussed at scientific conferences. But when its future landed on the table of the State Committee for Radio Electronics, the decision was brutal: Setun was put on a list of systems excluded from serial production.

The official justification was that it would be a “waste of funds”, even though the committee had never actually financed the project. Sobolev reportedly confronted officials, asking whether they had even seen the machine running. The answer was that there was no need: the right paperwork and signatures were enough.

In other words, the decision was not driven by performance, cost per FLOP or field reliability, but by alignment with a broader industrial plan. That plan favored binary architectures, closer both to Western designs and to the bulk of Soviet hardware development.

Even when the Czechoslovak government offered to manufacture Setun at scale at the Jan Šverma plant in Brno – with equipment ready to build hundreds of units per year – Soviet officials blocked the move. They argued that production had to remain domestic, despite having no intention of producing it themselves in any significant volume.

In 1965, production was quietly stopped. The design team only found out because customers started calling to complain that their orders had been cancelled. No scientific, technical or economic explanation has ever fully accounted for that decision.

Setun-70, Nastavnik, and the destruction of the original machine

Brusentsov did not give up on ternary computing. In 1967 he obtained approval for a new research project: Setun-70, with a clear deadline – have a refined ternary computer ready in under three years.

Setun-70 improved on the original in several areas:

- More RAM and a larger magnetic drum.

- User-programmable ROM pages.

- Lower power consumption and a more compact design thanks to a transistor-based power supply.

The team met the schedule and the new machine was working by early 1970.

From a systems perspective, however, the context had changed. The developer responsible for building the software environment for Setun-70 never delivered the expected tools, being absorbed by other projects. Leadership at the computing center also shifted: Sobolev, the original patron of Setun, had moved away from Moscow, and the new director had little interest in experimental architectures.

Brusentsov’s lab was evicted from its original facilities and relocated to a windowless attic in a student dormitory. They managed to take Setun-70 with them and built a system called Nastavnik (“Tutor”) on top of it, used for decades to handle didactic tasks such as assigning students to language classes according to level.

The fate of the first Setun was much harsher. In the summer of 1973, the prototype installed in the computer lab was shut down and dismantled. A logbook still exists, showing regular use with no downtime up to the last day, but the official order authorizing its dismantling has not been preserved. Researchers who later tried to reconstruct the story have not found a clear technical rationale for destroying a unique, functioning system.

What Setun still tells modern sysadmins

For a systems and infrastructure audience, Setun is more than a historical curiosity. It acts as a mirror for several very current issues:

- Designing for reliability under hard constraints: with ferrite cores, modest capacities and limited components, Setun still delivered years of stable operation in difficult environments.

- Alternative architectures vs. standardization: balanced ternary showed real benefits, but lost out to binary for reasons that had more to do with political and industrial alignment than with pure engineering.

- The impact of “minor” changes and integration shortcuts: the fan relocation story is a perfect example of how seemingly harmless tweaks can quietly break thermal design and availability.

- Politics, vendors and lock-in: Setun was cheap, reliable and validated, but it didn’t fit the dominant roadmap. It was crowded out not by benchmarks, but by decisions made far from the lab.

In an era that is once again exploring new architectures for AI workloads, multi-valued logic, specialized accelerators and aggressive power reduction, Setun is a reminder that technically superior ideas can be sidelined, and that architectural diversity is often lost in boardrooms, not in datacenters.

Frequently asked questions about Setun for systems administrators

What specific technical features made Setun different from other computers of its time?

Setun was the first universal computer based on balanced ternary logic, using trits (−1, 0, +1) instead of bits. It combined a ferrite-core RAM with 162 words of 9 trits and a magnetic drum with 1,944 words. Its ALU could perform additions and subtractions in about 180 microseconds and multiplications in roughly 320 microseconds, with support for floating-point arithmetic and a 24-instruction set including conditional jumps.

How did Setun handle memory and storage in terms of performance and reliability?

Setun’s ferrite memory acted as a fast random-access tier and, in practice, as a cache in front of the slower magnetic drum. Data arrived serially via paper tape, was converted to parallel form in a 9-trit shift register, and was then stored either in ferrite RAM or on the drum depending on program needs. Contemporary reports highlight the system’s stability: it passed three weeks of official tests without failures and ran for years in real deployments without regular manufacturer service.

If Setun worked, why wasn’t it mass-produced in the Soviet Union?

Although Setun passed official evaluations and was recognized as a universal ternary computer, the State Committee for Radio Electronics put it on a blacklist blocking serial production. A later offer from Czechoslovakia to manufacture it in volume was also rejected. Known justifications do not follow technical or cost arguments; instead they point to industrial policy and standardization choices that favored binary architectures aligned with the broader Soviet ecosystem.

What lessons does the Setun story offer to today’s system administrators and infrastructure leaders?

Setun shows that the “best” architecture from an engineering standpoint is not always the one that survives. Standardization, vendor ecosystems, and political or strategic considerations can override purely technical merit. It also reinforces the importance of respecting original thermal and mechanical designs, and of designing for resilience and maintainability, especially in environments with limited support. And it highlights the potential value of exploring non-standard architectures — for AI, embedded systems or low-power computing — even if they don’t neatly fit the dominant mainstream at first.

Sources:

– Notes and recollections by Nikolai P. Brusentsov on Setun and Setun-70.

– Historical technical descriptions of balanced ternary computing and Setun’s architecture and deployments.