The idea that GNU/Linux “consumes little RAM” often comes from a snapshot: you boot the system, open a system monitor, and you see surprisingly low numbers (especially with a lightweight desktop). But here’s the key nuance: Linux doesn’t just run on less memory — it also tends to use all available RAM as a system accelerator (caches, buffers, shared pages). And far from being a problem, that’s a big part of its efficiency.

On servers, this efficiency is obvious: with the same hardware, a smaller baseline footprint leaves more headroom for users and services. On a PC with 32 or 64 GB of RAM, the same logic still applies: every gigabyte that doesn’t disappear into “background noise” becomes headroom for real work (CAD, rendering, compiling, virtual machines, video editing, and more).

1) The key: “used memory” doesn’t mean “wasted memory”

Linux is designed to use free RAM as disk cache (page cache). This speeds up later reads of files, libraries, binaries, and recently accessed data. If an application needs memory, the kernel can reclaim that cache quickly and reassign it. This idea is often summed up by the classic “Linux ate my RAM”: “empty” RAM is wasted RAM, so the system prefers to convert it into performance.

Table 1 — How to read free without falling into traps

Indicator (as shown by free) | What it means in practice | Common mistake |

|---|---|---|

| used | Includes RAM used by processes and part of caches/buffers | Assuming “used” = “no RAM left” |

| buff/cache | Memory used to speed up I/O (can be reclaimed) | Thinking it’s “RAM permanently taken” |

| available | Estimate of RAM you can actually use without heavy swapping | Ignoring “available” and only looking at “free” |

A healthy Linux rule of thumb is: watch “available”, not “free”.

2) Why the “multi-user server” mindset also works on desktops

Your explanation is on the right track: many of the techniques that let a server serve many users with tight resources also apply to a single-user workstation.

(A) Shared pages and common libraries

On Linux, a lot of software shares libraries (code) in memory. When multiple apps use the same dependencies, they don’t duplicate everything: they can share pages.

(B) Real modularity (you load only what you need)

GNU/Linux lets you tune services, daemons, indexers, telemetry, visual effects, and more. A lightweight desktop often comes with fewer resident processes, less indexing, and fewer “always-on” components.

(C) Aggressive caching = better perceived performance

As soon as you start apps and open projects, cache starts working in your favor. That “Linux feels snappy” sensation often comes from the system reusing RAM to avoid disk waits.

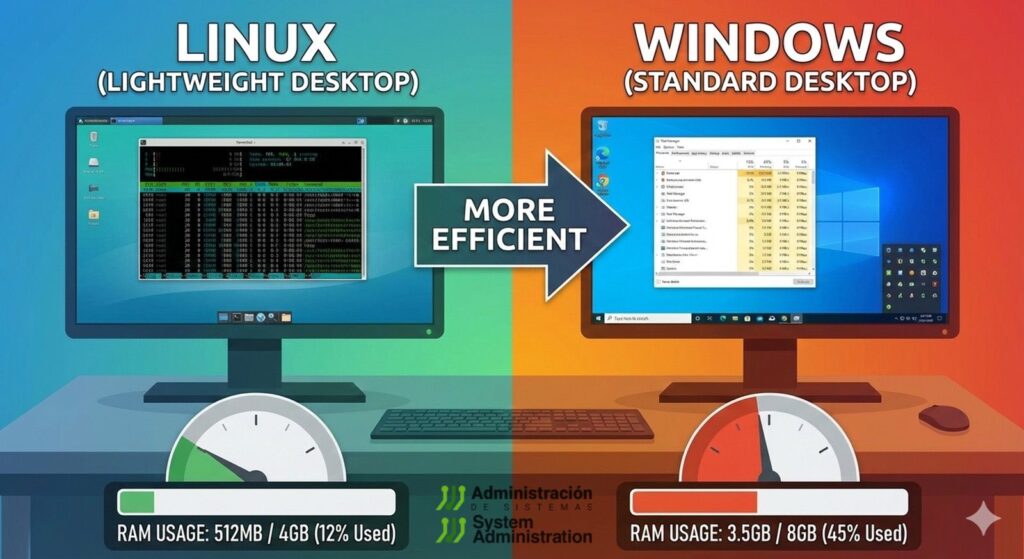

3) Lightweight desktops aren’t “only for old PCs”: they’re a strategy

The myth that “XFCE/LXQt/LXDE is for ancient hardware” comes from equating “lightweight” with “cut down.” But on powerful machines, a lightweight desktop can be a deliberate tactical choice:

- More headroom for heavy workloads: VMs, containers, rendering, compiling Chromium, running small model training, etc.

- Fewer background interruptions: indexers, animations, sync services, semantic search…

- Fewer spikes: some full desktop environments integrate more components that ramp up usage at login or during indexing

One point worth repeating: the idle difference matters less than the under-load difference, because a heavier desktop often brings more processes and more “noise” when the system is already stressed.

4) A practical comparison: what the “surroundings” typically consume

In real comparisons, baseline usage doesn’t depend only on GNOME/KDE/XFCE… but also on things like:

- Display manager (GDM/SDDM/LightDM)

- Network, printing, Bluetooth services

- Audio (PipeWire/PulseAudio)

- Indexing (Tracker, Baloo)

- Extensions, applets, compositing

- Integrations (portals, gvfs, sandboxing)

Tools like ps_mem are useful because they expose all the background “tolls” spread across daemons and desktop services (session managers, applets, device services, etc.).

Table 2 — A qualitative desktop comparison (focus and typical footprint)

Note: “footprint” here is a trend (low/medium/high). It varies a lot by distro, enabled services, and configuration.

| Desktop | Focus | Typical footprint | Ideal if… |

|---|---|---|---|

| LXQt / LXDE | Minimalism and speed | Low | You want maximum headroom for heavy apps |

| XFCE | Balanced: light but complete | Low–Medium | You want stability and control without extra weight |

| MATE | Classic and functional | Medium | You prefer a traditional workflow without big demands |

| Trinity (TDE) | Classic KDE3-style | Low–Medium | You want a classic desktop with a very small footprint |

| KDE Plasma | Full-featured and highly configurable | Medium (can be optimized) | You need power and customization |

| GNOME | Tight integration and uniform UX | Medium–High | You prioritize a modern workflow and extensions |

| Cinnamon | “Windows-like” experience | Medium–High | You want something familiar and comfortable |

| Budgie / Pantheon | Polished design and UX | Medium | You prioritize aesthetics and simplicity |

5) Measure properly: don’t stop at “RAM used right after boot”

If you want serious comparisons (and reproducible tables), measure the same scenario every time.

A simple, useful methodology

- Right after boot (don’t open anything)

- After 5 minutes (services that “wake up”)

- Browser + 10 tabs

- Your real workload (VMs, CAD, render, etc.)

Table 3 — Tools to measure memory “for real”

| Goal | Tool | What it adds |

|---|---|---|

| Big-picture view | free -h | Pushes you to look at “available” |

| Kernel-level detail | /proc/meminfo | Breaks down caches, slab, etc. |

| True per-process usage | smem (PSS) | Avoids misleading totals from shared memory |

| “Who’s eating it?” | ps_mem | Quick summary by process |

6) So why can Linux boot with so little RAM?

Beyond everything above, there’s a practical reality: GNU/Linux scales down easily. That matches the broader modular philosophy: you can run a lean stack, and only add what you actually need.

This doesn’t mean “Linux always uses little RAM.” It means it can — if you choose a lighter stack and don’t pile on background services.

Conclusion: “lightweight” doesn’t mean “old”; it means “headroom”

The better question isn’t “How much RAM does the system use?” but:

- How much RAM does your real workflow need?

- What stays resident without adding value?

- Which desktop gives you the best balance between productivity and background noise?

On a server, headroom becomes more users per GB. On a modern workstation, it becomes more margin for what actually matters: your applications, your projects, and heavy workloads.

FAQs (SEO / AI Overviews)

Which Linux desktop environment uses the least RAM on a modern PC with 64 GB?

Lightweight options like XFCE, LXQt, LXDE, or Trinity often make sense if you want to maximize headroom for VMs, rendering, or compilation. The advantage isn’t “it boots” — it’s that it tends to interfere less under load.

Why does Linux show so much RAM as “used” even when nothing is open?

Because it uses free RAM as disk cache to speed up the system. That memory can be reclaimed quickly when applications need it.

Does KDE Plasma use much more RAM than XFCE?

It depends heavily on enabled services (indexing, effects, applets). Plasma can be tuned quite a bit, but XFCE/LXQt usually come with less resident “ecosystem” by default.

How can I compare RAM usage between GNOME, KDE, and XFCE fairly?

Use the same distro and the same hardware (or the same VM), measure both at idle and after a few minutes, and compare using PSS (smem) and “available” in free — not just the “used” number.